In their 2024 annual report, the Canadian Fertility and Andrology Society released its Canadian Assisted Reproductive Technologies Register data. This data tracks almost all facets of assisted reproduction in detail (except for sperm donation).

Assisted reproduction occurs in all sorts of ways. In vitro fertilization, for example, takes a human sperm and a human egg, fertilizes them in a petri dish, and then transfers the embryo into the intended mother’s womb. Surrogacy is essentially the same thing, except the embryo is transferred to a surrogate mother who gestates and births the child before giving him or her up to his or her intended parents.

In our policy reports on in vitro fertilization and surrogacy, we’ve noted that these assisted reproduction techniques are morally problematic for all sorts of reasons. There is the philosophical question of whether children should only be conceived through sexual intercourse. There is the intentional freezing and destruction of embryos, which pro-life Christians who believe that life starts at conception must recognize as human beings. There is the high failure rate of IVF, leading to questions about how many unintentional deaths we are willing to tolerate to allow a new life to be born. There is the issue of using genetic testing to discriminate against some pre-born children who are likely to develop disabilities, chronic illnesses, or abnormalities. There is the practice of “selective reduction,” aborting a pre-born child if IVF leads to multiple pre-born children growing in the womb. There are physical risks of IVF to women, including a greater risk of developing ovarian cancer. There is an increased likelihood that children conceived through IVF will have genetic defects or intellectual disabilities. And there is the entire problem that IVF and surrogacy fracture fatherhood and motherhood; rather than one man and one woman laying claim to be the father and mother of a child, the intended father and mother, the genetic father and mother, and the birth mother all can lay some claim to being the parents of the child.

Given all these moral quandaries, we’ve suggested that IVF be greatly limited and surrogacy be banned entirely.

But in the absence of great restrictions on assisted reproduction, how prevalent a problem is it? Are there hundreds of thousands of children being conceived through IVF per year or just a few dozen? What is the survival rate of these children? How many people are turning to assisted reproduction?

Here’s some data.

In Vitro Fertilization

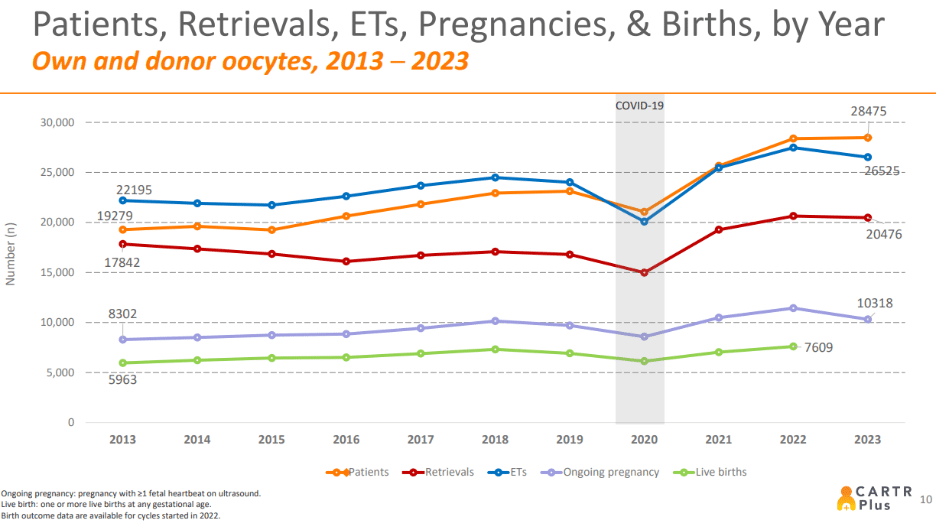

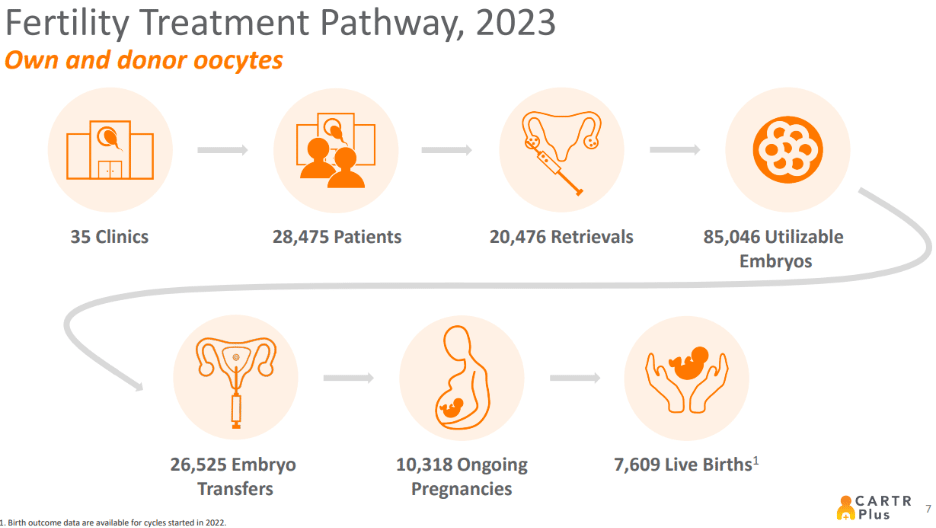

In vitro fertilization is becoming increasingly prevalent. Over 28,000 women visited these fertility clinics in 2023, and just over 20,000 egg (oocyte) retrievals were performed.

Perhaps most importantly, consider the number of live births compared to the number of embryo transfers (ETs). In 2022, approximately 27,500 embryo transfers – the transfer of an embryo from a petri dish into a woman’s womb – occurred, but only 7609 children were born. That is a “success rate” of only 28%. Only 28% of pre-born children survived the transfer. The remaining 72% – approximately 20,000 – pre-born children did not survive the implantation process.i

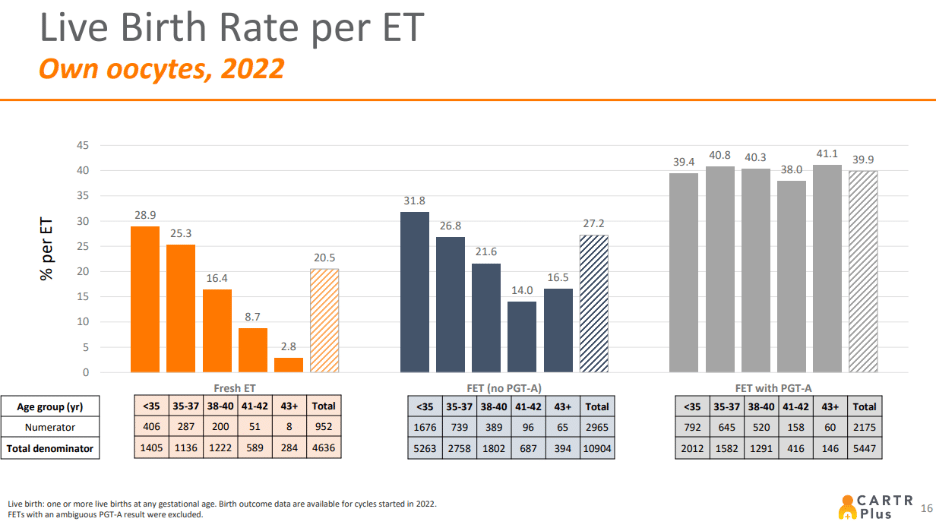

The following chart breaks this down by the age of the woman and the specific type of IVF. (Fresh ET means the embryos were never frozen before being transferred; FET (no PGT-A) means that the embryos were frozen but not genetically tested before being transferred; FET with PGT-A means that the embryos were frozen and only the embryos with the best genetics were transferred.)

Although the survival rate of the embryos is far higher if they are frozen and genetically selected, there are ethical problems with these two practices. If embryos are human beings, then it is just as immoral to freeze them in time as it would be to freeze an infant, a child, or an adult so that they stop developing. And testing embryos for genetic problems and implanting only the embryos with “good” genes is discriminatory. It avoids children with genetic deformities such as Down syndrome. It is a “transfer – and hence the survival – of the fittest.”

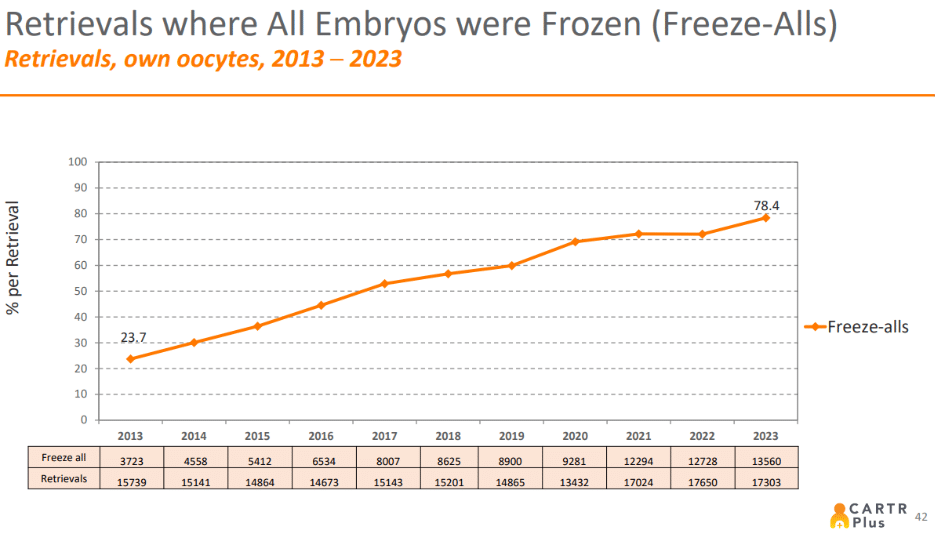

Unfortunately, since using frozen embryos that have been genetically tested and selected has the highest survival rate, an increasing percentage of all IVF treatments use frozen embryos. Almost 80% of all embryos are now frozen before transfer rather than being “fresh.”

But the survival rate of embryos – of pre-born children – is even worse than presented above. Only 28% of embryos transferred to a woman’s womb are born. But that ignores the fact that many more embryos are created than are ever transferred. Just consider the following summary graphic.

Over 85,000 “utilizable” embryos were created in 2023 (plus an unspecified number of embryos that were not considered “utilizable”). But there were only 7609 live births. Doing the math, that means that only 8.9% of all embryos created in a petri dish were born. Over 58,000 embryos that were created but not transferred were either destroyed (killed) or frozen (abandoned), and a further 20,000 accidentally perished in the process.

To put that into context, there were 101,553 abortions in 2023. Approximately 61,104 children in 2022 were in the foster care system. The intentional destruction of an embryo is the moral equivalent of abortion. Although the analogy is far less perfect, the foster care system is likely the most analogous to the long-term freezing of embryos. Both involve parents being unable or unwilling to take responsibility for their children. Many Christians give much thought to the injustice of abortion. Some mourn the brokenness of the foster system. But very few pay heed to the treatment of pre-born children in the assisted reproduction industry. And yet, the sheer number of mistreated embryos is comparable to the number of abortions or foster children.

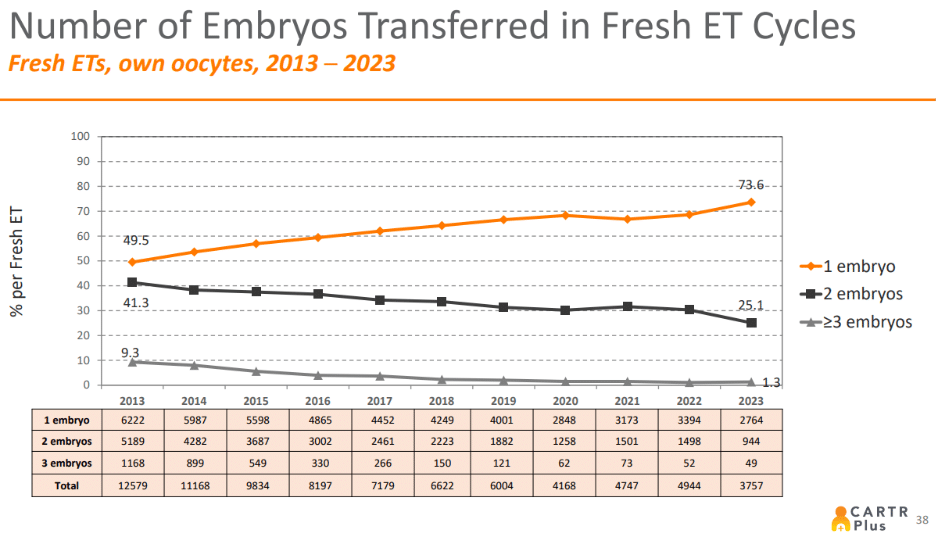

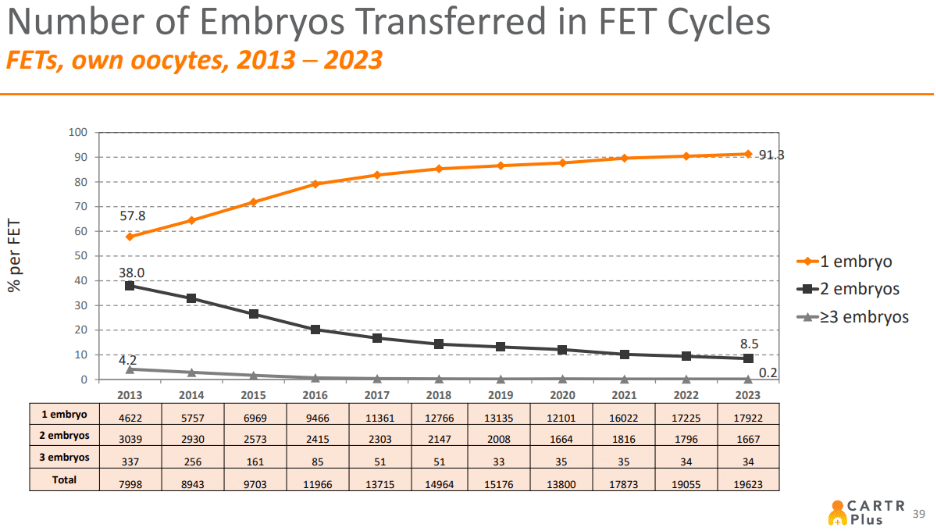

There is one small piece of good news in this report regarding IVF. In our policy report, we note that, “because of the risks involved in a multi-fetal pregnancy, women are commonly encouraged to ‘reduce’ the pregnancy – that is, they are encouraged to abort one or more of the children to increase the likelihood of a healthy pregnancy with a single child.” As a result, we recommended that only one embryo be transferred to minimize the motivation to have a “selective reduction” abortion.

At the time, we didn’t have any numbers to back up how common it was to implant multiple embryos. But the trend is in the right direction. Combining the rate of single “fresh” and frozen embryo transfers, only a single embryo is transferred 88% of the time. More than two embryos were transferred only in 0.35% of cases, making the circumstance in which there is a perceived “need” for a selective reduction abortion rare.

Surrogacy

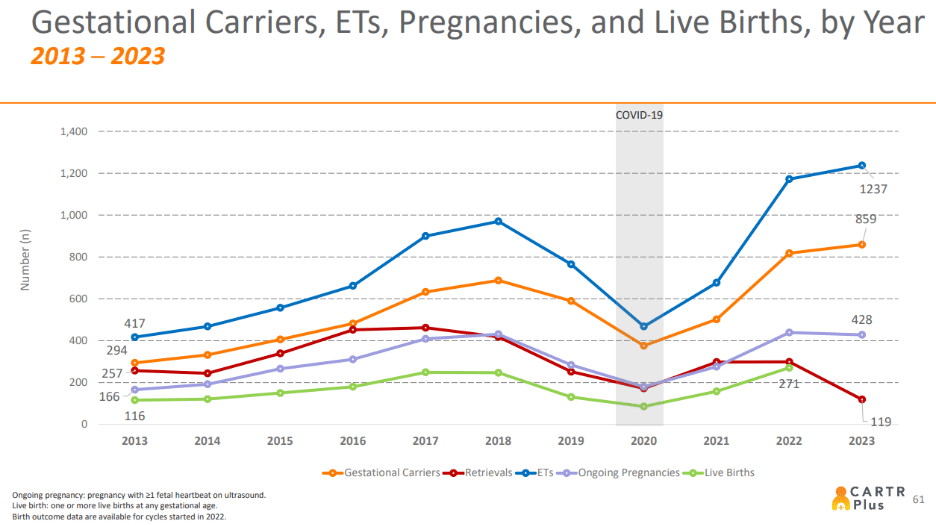

The report ends with some statistics on surrogacy (what the report calls gestational carrying). Gestational surrogacy occurs when a woman, unable to bear a child herself, contracts with another woman to carry her child on her behalf. A child is thus conceived by standard IVF practice and then transferred to the surrogate mother.

As demonstrated by the graph below, gestational surrogacy is far less common than standard IVF. In 2023, there were 859 gestational carriers (i.e. surrogate mothers). There were 1237 embryo transfers that resulted in only 428 ongoing pregnancies and 271 live births. That’s a “success rate” of 22%, slightly less than the 28% of standard IVF.

Conclusion

While an increasing number of Canadians are turning to assisted reproduction and more and more provinces are publicly funding the procedure, assisted reproduction is deadly. Far more pre-born children are frozen and intentionally or unintentionally killed than are born. Christians need not only to be aware of the magnitude of this tragedy but also speak up about it with their neighbours and elected representatives.

Parental Status is a Legal Construct

In Canada, “parental status” (the rights and duties of a parent) does not always attach to the person who is a child’s biological parent. For most people, becoming a parent in the real world and the legal world happens simultaneously. Two people get married, have a child, receive a birth certificate for their newborn, and life goes on – the law and the real world move along happily side-by-side.

Sometimes, however, the law simply does not match reality. There are times when the law partners with technological advances to legitimize human reproduction outside the bounds of the created order, like when couples use a surrogate to have a child. Surrogacy splinters parental status, especially for the mother. Instead of the genetic mother (the one who produces the ovum to be fertilized), the birth mother (the one who carries the child), and the “intended” mother (the one who is going to parent the child) being one and the same person, there can now be two or even three mothers.

Fracturing Motherhood Allows the Baby Business to Flourish

Canada passed the Assisted Human Reproduction Act in 2004, in an attempt to regulate certain “activities of concern” like human cloning or paying surrogate mothers. But it did not stop people from making business deals to have kids. Technically, Canadian law still forbids “renting” a woman’s womb to have a baby, but it’s been 10 years since that law was enforced. Renting of wombs does happen, with payment made informally because prospective parents are understandably worried about leaving a “damning paper trail.”

Couples who want a child but are unwilling or unable to be pregnant themselves can sign “surrogacy agreements” with a woman willing to act as a surrogate. These contracts state that the surrogate will give up the child upon birth. In most provinces, surrogacy contracts are recognized as valid evidence of parental status. In other words, if a surrogacy agreement has been signed, the province will issue a birth certificate that declares that the couple contracting for the child are the parents and have full parental status. The surrogate mother who has spent nine months of her life nurturing this child will have no parental status whatsoever. Sometimes these laws border on the bizarre. For example, in Ontario, the government will recognize a surrogacy agreement (and issue a birth certificate) that says that one child can have up to four different parents – one mom with three dads or four moms? – seemingly anything goes.

If you are interested in reading more about federal laws around surrogacy, please read ARPA Canada’s detailed surrogacy policy report or our much more brief one-pager.

Québec says “no”

Okay, so the federal government legalized altruistic (i.e., not paid) surrogacy in 2004. But were the provinces really required to recognize contracts that created multiple-parent families? No! In fact, Section 6(5) of the federal Assisted Human Reproduction Act explicitly permits provinces to legislate on the validity of all types of surrogacy agreements.

Québec stands out as a province that refused to allow for surrogacy agreements. Article 541 of the Quebec Civil Code simply said “[a]ny agreement whereby a woman undertakes to procreate or carry a child for another person is absolutely null” (emphasis added). Within Québec’s legal tradition, a declaration of absolute nullity is only applied to business arrangements that are contrary to public values. Québec took a moral position and legislated accordingly.

Frustrated with Québec’s approach, some people tried to skirt the law. One couple used a surrogate to have a child and did not write a name down in the “mother” section of the birth certificate. Then the intended mother petitioned the court to be allowed to adopt the child. For a time, the courts rejected these attempts as well.

Quebec Backs Down

Unfortunately, all this is set to change. Québec’s Assemblée Nationale is in the middle of passing Bill 12, which would grant parental status to all spouses or single persons who embark upon a “parental project” with a surrogate. This is sad news because it further entrenches the fracturing of motherhood and normalizes the intentional infliction of a “primal wound” on an infant child. Thankfully though, the Assemblée Nationale is avoiding a major mistake in provinces where surrogacy contracts are the norm. If Bill 12 passes, upon giving birth surrogate mothers would have the option of keeping the child and the written agreement she signed with the intended parents would no longer apply. ARPA Canada has noted that there are several reported cases of intended parents manipulating surrogate mothers or denying them any access to the child they carried for nine months. Bill 12’s renunciation option would serve as a corrective in these sad circumstances.

The Larger Lesson to Learn – Let’s Make Use of Federalism’s Gifts

Québec’s movement to sanction surrogacy agreements is disappointing. Still, there is a lesson to be learned from Québec’s last 19 years of disallowing surrogacy within its borders. There is a strange phenomenon in Canada where once the federal government decriminalizes something (think abortion and euthanasia), the provinces seem to feel the need to not only facilitate but also fund and promote that thing that was once criminal. However, the provinces simply do not need to do this. Québec, at least until Bill 12 passes, shows that it is possible to take a different path than the federal government on social issues.

It is important to note that, although the Assisted Human Reproduction Act stated that the provinces had permission to legislate on surrogacy contracts, constitutionally, Québec had the power to do that anyways. The power to legislate about contracts falls squarely within provincial jurisdiction. What if more provinces used their powers when it came to bigger social issues? For example, what if provinces exercised their power over the “establishment, maintenance, and management of hospitals” by inserting themselves into the MAiD conversation and pushed back with at least some restrictions? Most of public discourse, and certainly the talking heads, pretend that, because the Supreme Court struck down Canada’s prohibition on euthanasia, governments of all stripes are obliged to make death accessible to all. Again, this is simply not the case. To put it simply, MAiD happens in hospitals and is performed by doctors, and the provinces get to say how hospitals are run and how doctors are licensed.

There is a certain beauty to our federal structure because it allows for a government-to-government debate. Some provinces are more vocal than others, but the moral of the story here is this: just like Québec, the other provinces can be encouraged to speak up and take a stand on social issues that violate time-honoured moral codes and, by doing so, they can make a difference.

There are two different kinds of surrogacy: traditional and gestational. In traditional surrogacy, a child is created using the surrogate mother’s egg, resulting in a child that is genetically related to her. In gestational surrogacy, an embryo is created through in vitro fertilization (IVF)[1] and is implanted in a surrogate mother but genetically unrelated to her. Typically, a contract is signed in advance to designate who will be the legal parents of the child at the time of birth.

Together, surrogacy and IVF constitute what is called ‘assisted human reproduction.’ Like IVF, surrogacy is often seen as a way to overcome infertility in opposite-sex couples, and as a way for same-sex couples to have children. Through surrogacy, individuals or couples can commission a surrogate to carry a child for them, and the surrogate then gives the child up to the intended parent(s) after birth.

Commercial surrogacy, where a surrogate is paid for carrying a baby to term, is prohibited in Canada. Altruistic surrogacy, however, where a surrogate ‘volunteers’ to carry a baby without compensation, is permitted, and a surrogate can be reimbursed for expenses related to the pregnancy. In practice, it is difficult to differentiate between legitimate surrogacy expenses and illegitimate payments which incentivize women to become surrogates as a means of making income. The federal government recently increased possible incentives for surrogacy by expanding which expenses could be legitimately reimbursed.

ARPA Canada wants to draw attention to the commodification and exploitation of women and children that takes place through both commercial and altruistic surrogacy.

Relationships

Surrogacy fractures motherhood into multiple categories and reorders natural relationships. It ultimately puts the interests of the commissioning parents ahead of the interests of the child and the surrogate mother. Children are gifts to received from God, and a mother’s bond to her children is meant to be both biological and relational. Surrogacy disrupts this natural bond, compelling a woman to bear a child and immediately give it up after birth.

One surrogate’s story illustrates this problem: “I agreed to be a surrogate for a friend who was unable to conceive, using her husband’s sperm. I stayed attached after birth and breast fed my baby … I was supposed to surrender the baby to her for adoption by her. She can be the aunt, but I am the mother. I’m sorry in a way that it didn’t work out, but it didn’t.”

Commodifying Human Life

Through surrogacy, a woman’s reproductive capacities are reduced to a business asset. This not only often leads to major legal disputes but also treats a woman’s body as a ‘womb for rent.’ Even in altruistic surrogacy, women often suffer harm as they are pressured to behave as the intended parents desire and to give up the child they have carried.

Children who are born through surrogacy often feel abandoned by their birth mother and purchased by their legal parents. Children born through surrogacy may also be abandoned or at increased risk of abuse. One American couple commissioned a surrogate in Ukraine to have a child for them. The child had multiple disabilities and her American intended parents stated, “We will not take her to America. This baby is incurable.”[2] The child was left unwanted by both her intended parents and the surrogate mother. This is one example of what can happen when adults are not concerned with what is best for the child, but simply with their own desires.

Updated Policy Report

ARPA Canada has just released our revised and updated Respectfully Submitted policy report on surrogacy, explaining what it is and why it is bad public policy for both women and children.

Although commercial surrogacy is not permitted in Canada, various forms of commodification and exploitation through surrogacy still exist. ARPA Canada’s primary recommendation is that Canada prohibit all forms of surrogacy. Failing that, however, our recommendations focus on ensuring that human life is not commodified and that children are better protected throughout the surrogacy process.

We encourage you to read through the report and to send it to your MP and ask them to read it as well. Contact us at [email protected] if you have any questions or feedback.

[1] For more information on IVF, see ARPA Canada’s newly updated report.

[2] Lois McLatchie and Jennifer Lea, “Surrogacy, Law & Human Rights,” ADF International, 2022, p. 28.

After each federal election, the Prime Minister’s office releases Mandate Letters for each of the cabinet ministers. These letters explain the Prime Minister’s expectations for each member of his cabinet and lay out challenges and commitments that come with their role. At the same time, these letters are made publicly available so that Canadians can understand some of the priorities that the federal government will focus on over the next few years.

The ministers’ mandate letters were released on December 16, 2021. The basic template of each letter focuses on recovery from COVID-19, climate change, the rights of Indigenous Peoples, systemic inequity of minority groups within Canada, and general expectations for ministers. Many of the objectives and commitments in the letters are similar to what the government had promised prior to the election, so there are no major surprises. However, specific commitments are worth noting as we keep an eye on how they develop over the coming years.

Charitable Status

In line with the Liberals’ election promise regarding charitable status for certain organizations, the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance has been tasked with the following: “Introduce amendments to the Income Tax Act to make anti-abortion organizations that provide dishonest counselling to pregnant women about their rights and options ineligible for charitable status.” It’s unclear how exactly the government would remove charitable status from pro-life organizations or how far that would extend. However, the possibility is very concerning, and ultimately the government needs to recognize the value and importance of organizations like pregnancy care centres.

Hate Speech

Before the summer break in 2021, the government had introduced both Bill C-10 and Bill C-36, which focused on hate speech and regulating online content. Although those bills died when the election was called, the Liberals are once again focused on regulating and limiting freedom of expression both online and in public. The Minister of Housing and Diversity and Inclusion was given the following task: “As part of a renewed Anti-Racism Strategy, lead work across government to develop a National Action Plan on Combatting Hate, including actions on combatting hate crimes in Canada, training and tools for public safety agencies, and investments to support digital literacy, to prevent radicalization to violence and to protect vulnerable communities.”

In addition, the Minister of Justice will “continue efforts with the Minister of Canadian Heritage to develop and introduce legislation as soon as possible to combat serious forms of harmful online content to protect Canadians and hold social media platforms and other online services accountable for the content they host, including by strengthening the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Criminal Code to more effectively combat online hate and reintroduce measures to strengthen hate speech provisions, including the re-enactment of the former Section 13 provision.” This seems to be a replication of what was previously Bill C-36. However, there is a possibility that this legislation will include positive components around combatting online pornography as well as more negative limits on freedom of expression. ARPA Canada’s analysis of last year’s Bill C-36 can be found here.

The Minister of Canadian Heritage is expected to “reintroduce legislation to reform the Broadcasting Act to ensure foreign web giants contribute to the creation and promotion of Canadian stories and music.” The previous version of this legislation, Bill C-10, also included the possibility of regulating social certain private social media content that was determined to be a ‘broadcast.’ Further information around Bill C-10 can be found here.

We will be keeping watch to see what exactly is included in this type of legislation if and when it is introduced.

Pre-born Children

The government often speaks of ‘sexual and reproductive health’ to refer to abortion access. The recent mandates encompass that, and also specifically include issues such as in vitro fertilization and surrogacy. The Minister of Health is mandated to: “work to ensure that all Canadians have access to the sexual and reproductive health services they need, no matter where they live, by reinforcing compliance under the Canada Health Act, developing a sexual and reproductive health rights information portal, supporting the establishment of mechanisms to help families cover the costs of in vitro fertilization, and supporting youth-led grassroots organizations that respond to the unique sexual and reproductive health needs of young people.”

The Minister of Finance and the Minister for Women and Gender Equality and Youth are tasked with “expand[ing] the Medical Expense Tax Credit to include costs reimbursed to surrogate mothers for IVF expenses.”

One issue here is the clear plan to continue pressuring the province of New Brunswick to fund abortions in private clinics, something they are the only province not to do. More on that topic can be found here.

The focus on in vitro fertilization and surrogacy raises questions and concerns about how far these procedures might become commercialized in Canada. For further information on these issues, you can read ARPA Canada’s policy reports on both in vitro fertilization and surrogacy.

Gender and Sexuality

Regarding issues of gender and sexuality, the mandate letters only speak in broad terms, especially since Bill C-4, which banned so-called ‘conversion therapy’ was passed before the mandate letters were released. There is a lot of language around efforts to promote equality and remove discrimination for minority groups both in Canada and around the world.

The Minister of Justice is told to: “Build on the passage of Bill C-4, which criminalized conversion therapy, [and] continue to ensure that Canadian justice policy protects the dignity and equality of LGBTQ2 Canadians.”

The Minister for Women and Gender Equality and Youth is directed to “launch the Federal LGBTQ2 Action Plan and provide capacity funding to Canadian LGBTQ2 service organizations” and “continue the work of the LGBTQ2 Secretariat in promoting LGBTQ2 equality at home and abroad, protecting LGBTQ2 rights and addressing discrimination against LGBTQ2 communities, building on the passage of Bill C-4, which criminalized conversion therapy.”

It is hard to say what ‘building on the passage of Bill C-4’ looks like exactly because specifics are not provided. However, Bill C-4 is concerning on multiple levels, and building on it will likely follow in a similar vein. Further information on Bill C-4 can be found here.

Child Care

Child care continues to be an issue the federal government is pushing. The Minister of Families, Children and Social Development is tasked with concluding negotiations with provinces that have not yet signed an agreement with the federal government (Ontario and New Brunswick), and ensuring that $10-a-day child care is available throughout Canada. They also plan to “introduc[e] federal child care legislation to strengthen and protect a high-quality Canada-wide child care system.” You can read more about a Christian perspective on universal child care here.

Drug Use

The Minister of Mental Health and Addictions is tasked with advancing “a comprehensive strategy to address problematic substance use in Canada, supporting efforts to improve public education to reduce stigma, and supporting provinces and territories and working with Indigenous communities to provide access to a full range of evidence-based treatment and harm reduction, as well as to create standards for substance use treatment programs.”

This is not a new issue but there seems to be a new emphasis on it. Bill C-5, a reiteration of Bill C-22 from the previous Parliament, seeks to move increasingly towards treating substance abuse as a health issue instead of a criminal issue.

Conclusion

The issues presented here are priorities of the federal government, and they also raise various questions and concerns about what changes to legislation and regulations on these topics will look like. Stay tuned for further resources and action items as we see how these issues develop over the next few years.

by Nick Suk (ARPA intern)

Children are gifts from God, not products to procure or commodities to purchase. Procreation should take place within marriage, not through the deliberate fracturing of natural relationships. This biblical foundation is violated when a third party becomes part of the procreation process, either as a genetic parent (gamete seller or donor) or as a surrogate mother.

These are live issues in Canada today. MP Anthony Housefather has tabled Bill C-404 to decriminalize commercial surrogacy and the sale of gametes. The intent of the bill is to increase the number of people in Canada who supply gametes or become surrogates by permitting them to get paid for it. Mr. Housefather intends to make things easier for those who cannot have children on their own. His bill is not only based on a faulty religious foundation that idolizes individual choice, but it also assumes there are no dangers in commercializing surrogacy or commodifying gametes. The evidence suggests there are.

Employment or exploitation?

Some argue that Canada’s prohibition on commercial surrogacy creates a victimless crime. We criminalize such activity, however, in part because those who rent their wombs risk their own health and lives for monetary gain. The health risks these women take economically benefit “big fertility,” which makes billions globally each year on the commodification of wombs, babies and gametes. Certainly, other work involves risks as well, but surrogacy is different in kind. With other work, people are compensated for the “fruit of their labour”, for what is made or accomplished by their labour, but not for the use of their bodies by others. With surrogacy, a woman is either being paid for the use of her body, or for the child she bears, or both.

Pregnancy brings health risks. Ordinarily, women do not choose to take on the risks for financial gain, but rather receive from God the gift of a child as the fruit of sexual union. Surrogacy and in-vitro fertilization treatments bring additional dangers. Several embryos are often transferred into the surrogates with the hope that at least one implants in the uterus. This increases the chances of a multiples pregnancy, which can lead to abortions or premature labor and delivery. The surrogate contracts away the use of her body to “intending parents”, granting them a certain degree of control. Surrogates might be required to refrain from certain foods or activities, or even to abort an “extra” fetus or a fetus with a detectable disability.

Commercial surrogacy destinations, such as India and Thailand, have banned or proposed to ban commercial surrogacy because of evident exploitation. In India, women are frequently “pimped” into becoming surrogate mothers for foreign buyers. If Canada legalized commercial surrogacy, we would be in the minority of nations that permit paying women (or paying agencies which pay women) for the use of their wombs. France, Germany, and Italy have banned both altruistic and commercial surrogacy because of its inherent dangers.

History and foundations of Canada’s law

Our current law, the Assisted Human Reproduction Act, is based on the recommendations from the “Royal Commission on New Reproductive Technologies,” or the “Baird Commission,” which consisted of five women, all experts in relevant fields. The Commission’s recommendations were released at a time in which assisted reproduction technology was more novel, but their recommendations were based on timeless principles – for example, the importance of protecting vulnerable people against powerful commercial interests. They also wanted to ensure that the “profit motive is not the deciding factor behind the provision of reproductive technologies.” Once commercialized, some women will feel pressure to take significant health risks as a surrogate, mainly for economic reasons.

In the documentary “Breeders: A Subclass of Women,” produced by Jennifer Lahl, surrogates describe their loss of dignity and how they felt like tools for the intended parents. Their bodies became “hotels” for intended parents’ babies.

Commercial surrogacy also commodifies children. Unlike in adoption, “intended parents” pay a for-profit fertility clinic to match them with a surrogate who is willing to release her parental rights in exchange for money. Jessica Kern, a self-termed “product” of a surrogacy arrangement says her parents often carried a “we paid for you” mentality whenever she demonstrated dissatisfaction about not knowing her birth mother. Jessica’s human dignity was diminished. To Jessica’s parents, her birth mother was a service provider whom their daughter didn’t need to know.

Price-tags on children

Surrogacy also commonly involves the use of donor gametes, which brings further challenges to the children born through surrogacy. Anonymousus.org shares the stories of people who struggle with the knowledge that they have been intentionally deprived of any relationship with their genetic parents. One donor conceived person said, “It was crushing to learn that my dad got paid to participate in my conception.” Once gametes become commodified, more donor-conceived children will grow up not knowing their genetic parents and feeling like commodities.

Housefather has stated that it will be up to the provinces to regulate the surrogacy and gamete market once the Federal government decriminalizes it. With respect, this is reckless. There is no guarantee that the provinces will put in place regulations, thus risking the possibility that parts of Canada will have an unregulated market for reproductive technology. Unregulated surrogacy could mean poor background checks of intending parents or gamete donors and make it far easier for an abusive or unstable person to become a “parent”, essentially by purchasing a child.

Canadians are not entitled to have children by any practicable means. We should not allow greater risks to children and birth mothers by decriminalizing commercial surrogacy. It is one thing if a woman wishes to engage in such risks for altruistic reasons, but if impoverished women feel compelled to do so for economic reasons, then we are making a supposed reproductive right trump the dignity and best interests of Canadian women and children.

Take Action: Send an EasyMail letter to share your concerns with your MP

Bill C-404, “An Act to amend the Assisted Human Reproduction Act”, was introduced yesterday by Liberal MP Anthony Housefather.

If the bill passes, it will decriminalize commercial surrogacy and the sale of human gametes (sperm and eggs). This will allow women to enter commercial contracts to bear children for others in exchange for money. It will also allow paying people for their eggs or sperm.

The bill is short and simple and would do nothing to regulate these practices, except to specify that gamete donors and surrogates must be capable of consenting and not coerced, and the former must be at least 18 years old, the latter 21.

The bill raises many questions.

What would a market in human gametes look like? Would people with better health and higher IQs be able to make more donating their sperm and eggs? Are people going to shop for sperm and eggs based on donor profiles? How will this impact society’s view of human nature? Will younger, healthier women be able to demand higher pay for renting their womb? What portion of profits would go to a surrogacy agency and how much to the surrogate? What if the demand for surrogates is not met? Could the emergence of a market for womb rental result in vulnerable women being pressured into it? Even trafficked? Even if trafficking and coercion could be prevented, is it ethical to pay women to bear children to deliver to others?

ARPA Canada is concerned that this bill will risk the health and wellbeing of birth mothers and children for the following reasons:

- God designed reproduction to take place in marriage, as the fruit of bodily union between a man and a woman, and for children to know and be raised by their natural parents. Introducing third parties, either as sperm or egg donors or as surrogate mothers, crosses an important boundary and consequently leads to avoidable pain and confusion.

- Surrogacy commodifies women’s reproductive capacities. This is out of line with God’s good design for human reproduction and families. It undermines human dignity.

- Surrogacy agreements often restrain a woman’s autonomy by subjecting her to a specific diet, limiting or requiring certain exercise, possibly requiring her to abort one or several children, and to undergo a caesarian section delivery (the intended parents typically consider this the less risky option for the baby).

- Commercial surrogacy commodifies children as well. There should not be a price-tag attached to a child. The object of a surrogacy agreement is the delivery of a child to the paying party. Assisted reproductive services and surrogacy are provided in response to market demand, if the price is right, and the end product is a baby.

- Children born through surrogacy arrangements have expressed a sense of loss in not knowing their birth mother and knowing that their legal parents paid for them.

- Commercial surrogacy has been banned around the world because of how it leads to exploitation of women. Impoverished women are more vulnerable as they will be most prone to enduring the physical risks and emotional hardship of bearing a child for someone else. Very few countries allow commercial surrogacy, and some that have allowed it in the past such as India, are now restricting it to curb exploitation.

- Gamete commodification is damaging to the dignity of the children and dehumanizing. For one, it separates children from their genetic parents intentionally and by design. It also leads to a “designer baby” mentality, where people choose what kind of people they want “their” baby’s DNA to come from (smart, athletic, black, white, tall, short, etc.). It makes children a product to which people feel entitled, rather than the fruit that crowns marriage and is received from God as a good and sacred gift.

- For a woman, gamete donation requires drug-use, hormone treatment, and invasive medical procedures, which can have long-lasting medical effects. For a man, it typically involves pornography and masturbation.

Have questions? Contact us at [email protected]

For more information, read ARPA’s policy reports, “Surrogacy” and “In Vitro Embryo”.

*Correction: The first version of this article (May 30) stated that Bill C-404 did nothing to regulate surrogacy or gamete donation; the corrected version (June 1) notes that the bill includes consent and age requirements for donors and surrogates. We certainly did not mean to imply that the bill would permit the participation of minors or the mentally incapable. ARPA apologizes for the inaccuracy.*

If you agree take just five minutes right now and send this EasyMail letter to your MP, urging them to carefully consider this bill and the issues it raises and speak up in defense of human dignity and vulnerable persons.

- How will Bill 28 affect me and my family?

- Are “natural families” and “natural parents” really so important? What about adoptive parents?

- Isn’t the main purpose of the bill to simplify the process for both partners in a same-sex couple to be recognized as parents?

- Bill 28 facilitates having children through surrogacy. What’s the problem with that?

If you have not read ARPA’s main article on Bill 28, we encourage you to read it first. There you will also find links to EasyMail letters on this topic. If you have already emailed your MPP, you can use this FAQ to assist you as you follow up with an additional email or phone call.

How will Bill 28 affect me and my family?

Bill 28 does not simply create or add new kinds of families. It redefines all families, present and future. By removing references to “mother”, “father”, “natural parents”, and “blood” relations from Ontario law, and by creating alternative, contractual “families” between multiple unmarried and unrelated adults and children conceived further to their “parentage agreements”, Bill 28 knocks family law even further off its foundations.

The bill gives the illusion of greater freedom. It gives people more “options” to choose from as they determine what a family is for them. But if the state can redefine the family and offer more “options” or “rights” by knocking family law off its foundations of marriage and blood relations, it can also take rights away. What will become of parental rights if a “family” is whatever the state says it is and a “parent” is whoever the state says is a parent? It’s hard to know, but it’s deeply disconcerting.

Do we care about our children and grandchildren’s understanding of who they are, what a family is, and why it’s important? Make no mistake, education policy and curriculum (among other government policies and programs) will fall in line with Bill 28’s radical changes to Ontario law. This is about more than immediate practical consequences to my parental rights or yours – it is about embedding a false understanding of who we are as human beings into the law.

According to a leading family law textbook, family law has traditionally been concerned with “the relationships between husband and wife and parent and child.” And, “The main subjects of family law have, therefore, traditionally been marriage, separation and divorce, property rights of spouses during the marriage and on marriage breakdown, support obligations of spouses to one another, the care and custody of children, support obligations of parents to their children, the intervention of the state in the parent-child relationship through child protection legislation, and the establishment of a parent-child relationship through adoption.” (Hovius on Family Law, 7th edition)

Bill 28 will impact many and likely all of these areas in the long term. It makes marriage, which our law and culture have been devaluing for decades, even less important in family law. Far less. Marriage-plus-children will no longer be the basic model (which the law of common law relationships and adoption reflect). Having children the way almost everyone in the world does will be considered in Ontario law to just be one way (and no more legitimate or desirable) among others to form a “family”. The “natural family” and “natural parents” are not to be favoured, promoted, or given primacy in law. Bill 28 rejects the very idea of a natural family.

Bill 28 declares all “families” – whatever voluntary arrangements the state deems worthy of the term – “equal”. So it renders marriage, common law relationships, and blood relations – the foundations for family law – unimportant in law. Of course people can still form families by getting married and having children under Bill 28. But the philosophy of Bill 28 is that you are not family because you are married or related by blood. (Hence the removal of references to relations “by blood” and to “natural parents”.) Rather, you are family if the law says you are. And if the law says you are family, your family is “equal” to all other families. If the state one day says you are not a family or you aren’t parents – even to your own biological children – what will you say?

Are “natural families” or “natural parents” really so important? What about adoptive parents?

Emphasizing the importance of biology and blood relations between children and parents sometimes raises questions about adoptive parenting. Properly understood, however, adoption does not undermine the “conjugal conception of parenthood” or the natural family, but affirms the good of both.

In an adoptive family, too, it is marital love that is the starting point for the family, Dr. Tollefsen explains. The mutual commitment of spouses to each other and the child is what initiates the familial relationship, whether the child is the biological fruit of marital love or grafted into that relationship of mutual love and commitment through adoption.

Adoption should not be understood as a way to remedy the “problem” of infertility. Rather, adoption is for the good of the child. Adoption integrates children into a family who would otherwise not have a family. Affirming the good of adoption does not require redefining the family. It does not require throwing aside conjugal union as the foundation of the family. Adoption ideally provides the child both a mother and a father (other considerations being equal). Placing the child with relatives is also desirable where possible – again, because blood relationships do matter.

We recognize adoption to be a good alternative for a child where the child’s natural parents are deceased or unable or unwilling to care for the child, but the law prioritizes and protects the child’s relationship with his or her natural parents and should continue to do so.

Even when children are adopted, we generally recognize the good of the child learning in time who his or her natural parents are, for health and identity reasons. Bill 28 does not provide for this.

Bill 28 designs a legal system that legitimizes and encourages deliberately bringing children into the world who are separated at birth from their mother and father and whose legal parents may have no relationship beyond the merely contractual. Adoption, conversely, is intended to provide a child with a family in place of the child’s natural parents where the latter are deceased, unable, or unwilling to care for the child, without denying the reality that the child does in fact have biological and adoptive parents (categories that Bill 28 erases).

Bill 28 may even make it more difficult for some couples to adopt children. If a couple holds the view that children do best when raised by a married mother and father (a view supported by the evidence), or even that children are better off with a married couple as parents than a group of four co-signors of a contract, their views would be plainly contrary to the “All Families Are Equal Act”. Consequently, it may be considered contrary to public policy to place adoptive children with people who hold such beliefs. See for example this story out of the United Kingdom.

Isn’t the main purpose of the bill to simplify the process for both partners in a same-sex couple to be recognized as parents?

Currently, if a same-sex couple wishes to have a child that is legally recognized as the child of both of them, they can either adopt a child together or one of the two can be the biological parent of a child with a third party. In the latter case, the non-biological parent of a same-sex couple has to apply to a court to be recognized as a legal parent, effectively legally adopting the child. Also, when a birth is registered in Ontario, the law requires parents to list a mother and a father. This means that same-sex couples cannot both be listed on the birth certificate.

With opposite-sex couples, conversely, the child’s mother’s husband or common law partner is presumed to be the child’s father, unless evidence is presented to the contrary. Both mother and father can be listed on the child’s birth certificate.

The differences are derided by some as discriminatory and unjust. In our view, however, the differences arise not from any irrational animus towards or mistreatment of LGBT persons, but from the real differences between opposite and same-sex couples and the reality that every child has a biological mother and father. One or both of the partners in a same-sex relationship must inevitably be an adoptive parent.

If the goal were simply to save same-sex couples the cost and inconvenience involved in having both partners recognized as legal parents, Ontario could simplify adoption procedures and provide additional support for parents going through that process.

But Bill 28 goes way beyond making things easier for same-sex couples. In fact, as explained elsewhere, it makes couples (opposite-sex or same-sex) far less important in family law overall, opening up alternative contract-based “families” between multiple parties who are not in a committed relationship or related by blood.

Bill 28 facilitates having children through surrogacy. What’s the problem with that?

Surrogacy is a difficult and complex issue, legally and ethically. If the Ontario government is interested in reforming the law of surrogacy, it should at least study the matter in depth and allow time for public input first. Here are some of the problems with surrogacy.

Essentially, surrogacy commodifies women and children. It makes a woman’s reproductive organs objects than can be used and rented. It risks causing disruption in the lives of children born through surrogacy. It can even leave children vulnerable to trafficking. According to international law, surrogacy violates human dignity and children’s best interests, as Adina Portaru (PhD in international law) explains:

Surrogacy under Bill 28 will likely cause substantial confusion and conflict.

Many persons might claim parental rights with respect to a child born out of a surrogacy agreement under Bill 28: the surrogate mother, the genetic mother (egg donor), the husband or common law partner of the surrogate mother (presumptions of paternity), the genetic father (sperm donor), and the four “intended parents” signatory to the surrogacy agreement.

Bill 28 encourages surrogacy and facilitates the establishment of families through “surrogacy agreements” with up to five parties – four “intended parents” plus the surrogate. This new form of family, which has no couple in a committed relationship at its core, depends on women agreeing to be “breeders”.

Other countries such as France, Finland, Iceland, and Germany, completely prohibit surrogacy, recognizing that even altruistic surrogacy can be exploitative and lead to serious conflict. Quebec law does not recognize surrogacy arrangements and does not enforce surrogacy contracts. France does not allow people who arrange to have a child through a surrogate to be recognized as the child’s parents at birth or to adopt the child.

Ontario would do well to at least have a legislative committee study why some jurisdictions have prohibited surrogacy while others have permitted and regulated it.

The Ontario government is fast-tracking a bill that, if passed, will fundamentally overhaul family law in Ontario. It is critical that we understand these changes and seize the narrow window of opportunity to share our concerns with our leaders before the legislation becomes law.

Bill 28, the Orwellian “All Families Are Equal Act”, removes the term “mother” and “father” from all Ontario law, to be replaced with “parent”. The bill also eliminates the basic assumption of Ontario law that a child has no more than two parents. It eradicates the traditional categories of natural or adoptive parents and removes all references to persons being the “natural parents” of a child and to persons being related “by blood”. The French version replaces uses of the term “parent de sang” (parent of blood) with “parent de naissance” (parent of birth).

be replaced with “parent”. The bill also eliminates the basic assumption of Ontario law that a child has no more than two parents. It eradicates the traditional categories of natural or adoptive parents and removes all references to persons being the “natural parents” of a child and to persons being related “by blood”. The French version replaces uses of the term “parent de sang” (parent of blood) with “parent de naissance” (parent of birth).

The bill allows up to four people to enter a “pre-conception parentage agreement” (PCPA) to be recognized as a child’s parents at the time of the child’s birth. It also allows up to four “intended parents” to enter a “surrogacy agreement” with a surrogate who agrees to relinquish parentage after the child is seven days old. The bill separates biological from legal parentage in these and other ways.

Under the bill, a child can have up to four “parents” at birth where two, three, or four parties agree in writing to be parents to a child yet to be conceived.[

The bill requires the “birth parent” (the “person who gives birth to the child”, not necessarily the biological mother) to be a party to a PCPA and therefore a legal parent. (This is not the case with surrogacy agreements, as explained further in the next section of this article.) If the child is to be conceived “without the use of assisted reproduction” (i.e. naturally), the law also requires “the person who intends to be the biological father of the child” to be party to the PCPA. If assisted reproduction is used, the biological father need not be a party to the PCPA.

In a PCPA, the spouse of the “birth parent” also need not be a party to the agreement (and thus not a parent to the child) if he or she provides written confirmation before the child is conceived that he or she does not consent to be a parent of the child.

This means that a child at birth can have four legal parents, one of whom is the child’s birth mother (but not necessarily biological mother), plus three other adults of no familial relation to the birth mother. It is possible that not one of a child’s 4 “parents” under a PCPA will actually be the child’s biological parent, since outside donors of “reproductive material or an embryo” can be used. It is possible that the “birth parent’s spouse” is not a parent to the child, while up to 3 other persons are.

(Note that none of the two to four parents in a PCPA is considered an adoptive parent; adoption is a separate matter.)

Surrogacy agreements

A “surrogacy agreement” as defined by Bill 28 means a written agreement between a surrogate and one or more persons respecting a child to be conceived by assisted reproduction and carried and borne by the surrogate in which the surrogate agrees to not be a parent of the child and the other parties agree to be parents.

Unless the surrogacy agreement provides otherwise, during the first seven days after a child’s birth, the surrogate and up to four “intended parents” share the rights and responsibilities of parents. Any provision of the surrogacy agreement respecting parental rights and responsibilities is of no effect after this initial seven-day period.

There can be up to four “intended parents” signatory to a surrogacy agreement, and the surrogate cannot be among them (if she were, it would be a PCPA). However, the surrogate legally has a presumptive “entitlement to parentage” which she can relinquish by consent in writing only after the child is seven days old. Even if she agreed beforehand in a surrogacy agreement to relinquish entitlement to parentage, that agreement is not binding.

It is only after a “declaration of parentage” is received from a court that the parties to a surrogacy agreement can actually become the legal parents of “the child contemplated by the agreement”. Such a declaration is not to be made until the surrogate provides consent in writing to the intended parents that the child becomes the child of each intended parent and ceases to be the child of the surrogate. A court can waive the requirement for the surrogate’s consent, however, if the surrogate is deceased, cannot be located, or refuses to give consent.

Any party to a surrogacy agreement including the surrogate may apply to a court for a “declaration of parentage”. The court may grant the declaration that the applicant request or “any other declaration respecting parentage of a child born to the surrogate as the court sees fit.” When it comes to whom a court will declare to be a child’s legal parents, “a surrogacy agreement is unenforceable in law”, although it can be used in court as evidence of an intended parent’s intention to be a parent or a surrogate’s intention not to be a parent. In every case, the court’s “paramount consideration” in making a declaration of parentage must be “the best interests of the child”.

Surrogacy agreements as provided for in Bill 28 mean that a child can have (seven days after the child’s birth) up to four legal parents, none of whom is the child’s biological father or mother or birth mother.

Further separating biological and legal parentage

We have already seen how “pre-conception parentage agreements” and “surrogacy agreements” separate biological parentage from legal parentage. But Bill 28 separates natural and legal parentage in other ways too. (Note that we are not talking here about adoption—a legal mechanism traditionally intended to provide a child with parents in place of the child’s natural parents where the latter are deceased or are unable or unwilling to care for the child.)

Bill 28 provides that a person who provides “reproductive material or an embryo for use in assisted reproduction” shall not, simply by being a biological parent, be recognized in law as a parent of the child, unless “the provision of reproductive material or embryo was for his or her own reproductive use.”

The law also allows a man to father a child by natural means, but to agree in writing before conception to not be a legal parent of the child. The law calls a sexual act intended to conceive a child further to such an agreement “insemination by a sperm donor”.

The law provides no registry for recording a child’s natural father or mother. Children conceived by donors of “reproductive material or an embryo” or by “insemination by a sperm donor” may never learn who their natural parents are or in the latter case, who their natural father is.

The many ways the bill is bad for children

Bill 28 commodifies children – objects to be produced and possessed.

Children have an innate desire to know who their natural parents are and should not be deliberately deprived of that knowledge. Children need stability in the home. A divorce between a child’s natural parents can be disruptive enough and can cause great distress to the child, damage their trust, hurt their performance in school, and so on. What about fights between up to four “parents”, none of whom ever married any of the others?

How can any of this be considered to be “in the best interests” of children yet to be born? Is this the legal framework into which people should intentionally bring children?

The bill also denies the reality of sexual difference. It removes the terms “mother” and “father” from Ontario law completely, reflecting the government’s view that there is no difference between a mother and a father and that a child does not need both.

The bill also completely discounts the important link between marriage, or even a long-term committed relationship between two people, and the healthy upbringing of children.

Under this bill, a child’s four parents could be tied to each other by nothing but a common desire to be a co-parent of a child, who is perhaps conceived in a lab with “reproductive material” from anonymous donors. The bill has the Orwellian title All Families Are Equal Act, but how is a “parenting” contract between up to four unrelated parents a family?

Of course, many children lack a mother or a father because of death or abandonment. But it is another thing entirely to design a legal system that legitimizes and encourages deliberately bringing children into the world without a mother or a father or even a relationship between the child’s parents that is more than merely contractual. And even if we call a parenting agreement between four men or women a family, it is not equal to the natural family, nor the adoptive family.

The bill makes children likely objects of litigation

Children born into these new “family” arrangements are much more likely to be the objects of litigation before and after birth, and throughout their childhoods. One can imagine several litigation questions that could easily arise.

When a child is born, is that child “a child contemplated by” the pre-conception parentage agreement or surrogacy agreement? Was the PCPA or surrogacy agreement properly formed? Were the essential terms properly understood and agreed upon by all parties? Did any of the parties sign under duress or undue influence? Did any of the parties rescind the agreement before “a child contemplated by” the agreement was conceived?

What if the biological mother and biological father decide, after conceiving a child, that they want the child to be theirs alone, despite having signed a pre-conception parentage agreement with two other persons before the child was conceived? Such a change of mind could occur shortly after conception, birth, or years later when disputes with the other “parents” arise.

What do shared “parental rights and responsibilities” between four “parents” (related or unrelated to each other) look like in practice? What about four “intended parents” and a surrogate? How can custody be fairly arranged between four different parents, none of whom are necessarily married to or otherwise related to any of the others? What happens when one or more of the four wants out?

There will be some degree of uncertainty wherever a surrogacy agreement is used. Surrogacy agreements are not binding in law. A surrogate may refuse to consent in writing to relinquish entitlement to parentage.

Even if the surrogate does relinquish parentage after the child is born, it is not difficult to imagine litigation occurring thereafter, with a surrogate arguing that her consent to relinquish parentage is not legally binding because she was under undue influence, duress, or was not of sound mind. And what if the surrogate is also the egg donor (i.e. the biological and birth mother)? There is no rule against that.

Bill 28 being fast-tracked to avoid scrutiny

Bill 28 passed first reading on September 29th, second reading on October 3rd, and was considered by the Standing Committee on Social Policy on October 17-18. All that is left is for it to receive clause by clause consideration on October 24 and 25 before it goes back to the Legislature for third reading and final vote before it becomes law. The fundamental building block of society, the most basic social institution – the family – must not be so totally redefined by an omnibus bill that is rammed through in a month.

The bill is obviously being fast-tracked intentionally to avoid public scrutiny.

We urge all Ontarians to contact their member of provincial parliament (MPP) to communicate your concerns immediately. Click here to see several EasyMail drafts, which we invite you to personalize and change as you like, and send to your MPP. And when you have done so, send a note to your friends and fellow church members, urging them to do the same. If you have an additional 10 minutes for this crucial issue, make a phone call to your MPP in a few days, asking if they have read your letter and asking them to do so before they vote. Find your MPP here.

EasyMail letters:

- Concerns with Bill 28 (letter)

- Bill 28 harms children (letter)

- Bill 28 undermines the family (letter)

- Bill 28 is insulting to women (letter)

Graeme Hamilton, National Post Published: Thursday, March 12, 2009

MONTREAL • The Quebec couple had tried everything to conceive a baby since marrying in 2002 – surgery, artificial insemination, in-vitro fertilization. When their attempts failed, they turned to the Internet and found a woman willing to serve as a surrogate mother in exchange for $20,000. The surrogate was artificially inseminated with the husband’s sperm, and last year she gave birth to a healthy baby girl.

The baby was immediately turned over to the couple, with only the father’s name listed on the birth certificate. All that remained was to have his wife adopt the infant, and the couple would be legally recognized as her parents. [Keep reading this story here.]