The American Supreme Court continues to be busy. After upholding the legality of an age-verification law to limit access to pornography in Paxton and a ban on medical transitioning for minors in Skirmetti, the U.S. Supreme Court recently tackled gender and sexuality ideology in education. In Mahmoud v Taylor, the Court ruled 6-3 that requiring students to receive “LGBTQ+-inclusive” teaching with no opt-out violated the free exercise of religion.

Overview of the case

The Montgomery County school board in Maryland, adjacent to Washington DC, oversees one of the largest school districts in the United States. The district enrolls over 160,000 students and has an operating budget of almost $3 billion. The Board approved “LGBTQ+-inclusive” storybooks for the K-5 classroom (students aged 5-11). These books affirm same-sex relationships and transgender identities. Teachers were expected to use these books as a part of their classroom instruction and to affirm LGTBQ+ identities. For example, “If a student claims that a character ‘can’t be a boy if he was born a girl,’ teachers were encouraged to respond: ‘That comment is hurtful.’”

At first, the Board notified parents when these books would be used in class so that they could opt their children out of those classes. Many parents believed that these resources were “implying to [children] that their religion, their belief system, and their family tradition is actually wrong.” But the board rescinded the opt-out policy within a year.

Various parents – two Muslims, three Roman Catholics, one Ukrainian Orthodox – who had children in the school district challenged the constitutionality of the lack of an opt-out. They claimed that indoctrinating children with a pro-LGBTQ+ worldview violated their constitutional guarantee to the free exercise of religion.

Their argument goes something like this: 1) their religious beliefs include specific beliefs on gender and sexuality, 2) their religious beliefs require them to educate their children in these beliefs, and 3) the use of “LGBTQ+-inclusive” storybooks undermines these beliefs, 4) therefore, the Board’s requirement that all students be subjected to “LGBTQ+-inclusive” teaching violates their right to the free exercise of religion. Here is how the Court sums up the Petitioners’ beliefs:

Mahmoud and Barakat are Muslims who believe “that mankind has been divinely created as male and female” and “that ‘gender’ cannot be unwoven from biological ‘sex’—to the extent the two are even distinct—without rejecting the dignity and direction God bestowed on humanity from the start…” [I]n their view, “[t]he storybooks at issue in this lawsuit . . . directly undermine [their] efforts to raise” their son in the Islamic faith “because they encourage young children to question their sexuality and gender . . . and to dismiss parental and religious guidance on these issues.”

Jeff Roman is Catholic. And Svitlana Roman is Ukrainian Orthodox. They believe that “sexuality is expressed only in marriage between a man and a woman for creating life and strengthening the marital union… that gender and biological sex are intertwined and inseparable” and that “the young need to be helped to accept their own body as it was created…” [A]llowing those teachers to “teach principles about sexuality or gender identity that conflict with [their] religious beliefs” would “significantly interfer[e] with [their] ability to form [their son’s] religious faith and religious outlook on life.”

The Persaks are Catholics who believe “that all humans are created as male or female, and that a person’s biological sex is a gift bestowed by God that is both unchanging and integral to that person’s being…” They are concerned that the Board’s “LGBTQ+-inclusive” storybooks “are being used to impose an ideological view of family life and sexuality that characterizes any divergent beliefs as ‘hurtful.’” They think that such instruction will “undermine [their] efforts to raise [their] children in accordance with” their religious faith.

The parent petitioners in this case… all believe they have a “sacred obligation” or “God-given responsibility” to raise their children in a way that is consistent with their religious beliefs and practices.

The guarantee of the free exercise of religion disallows attempts to compel children to abandon their religious beliefs. For example, in the 1943 Barnette decision, the Court ruled that schools could not require Jehovah’s Witnesses to salute the American flag, which they considered to be a “graven image.”

But the court was clear that this constitutional right goes beyond policies that compel children to abandon or violate their religious beliefs. It also “protects against policies that impose more subtle forms of interference with the religious upbringing of children.” A classic 1972 freedom of religion case – Yoder – allowed Amish parents to take their students out of school after eighth grade, despite a state law that required school attendance until age 16. The Amish parents reasoned that “the values taught in high school were ‘in marked variance with Amish values and the Amish way of life,’ and would result in an ‘impermissible exposure of their children to a “worldly” influence in conflict with their beliefs.’”

The Court in Mahmoud decided that pressuring students to adopt a pro-LGBTQ+ worldview is a similar infringement on the free exercise of religion. “The [“LGBTQ+-inclusive”] books are unmistakably normative. They are designed to present certain values and beliefs as things to be celebrated, and certain contrary values and beliefs as things to be rejected.”

This accords well with the Reformed recognition that no teaching can be truly neutral. There is a worldview underlying the sexual revolution and the gender revolution. Rather than trusting God’s Word and general revelation as the authority for morality and truth, the LGBTQ+ position boils everything down to feelings. For instance, two of the LGBTQ+-inclusive” storybooks insist that same-sex marriage must be permissible if two men “love each other” and accepting another person’s gender identity “is about love.”

The majority opinion dismisses various arguments in defense of the Board’s mandatory “LGBTQ+-inclusive” education. These resources are not simply “exposure to objectionable ideas… The storybooks unmistakably convey a particular viewpoint about same-sex marriage and gender.” Constitutional guarantees do not stop at the schoolhouse door. The fact that parents can educate their children elsewhere (e.g. in a private school or at home) does not mean that the public school can exclude children of religious parents. “Public education is a public benefit, and the government cannot ‘condition’ its ‘availability’ on parents’ willingness to accept a burden on their religious exercise.”

Room for improvement…

Unfortunately, the Court doesn’t bother to further apply its claim that education cannot be neutral. For example, the Court tries to be neutral on these matters of gender and sexuality. “We express no view on the educational value of the Board’s proposed curriculum, other than to state that it places an unconstitutional burden on the parents’ religious exercise if it is imposed with no opportunity for opt outs.”

This decision also isn’t the final word on this matter. Rather than ruling definitively on the constitutionality of requiring children to be fed an “LGBTQ+-inclusive” worldview, this case only grants a temporary injunction. It requires the Board to notify the parents in the case – but not necessarily other religious parents – if “LGBTQ+-inclusive” storybooks will be used in the classroom and allow these parents to opt their children out of those classes until the main issue is decided. This isn’t necessarily a criticism of the Court. The parents were asking for such an injunction. But it means there is still more to do to protect religious freedom south of the border.

…But still better than here in Canada

Canada is still several steps behind the United States in preserving the religious freedom of its citizens and combatting the sexual revolution and gender revolution. Teaching about sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) is rampant in public schools across the country, particularly in British Columbia and Ontario. Only Alberta has taken significant steps to remove gender ideology from classrooms. They now require all materials related to gender and sexuality to be approved by the Ministry of Education, and schools must obtain parental opt-in before teaching these subjects.

Canadian courts have not yet weighed in on the issue, though they likely will soon, since a couple of LGBTQ+ organizations have voiced their intention to challenge Alberta’s policy. Canadian courts could use similar reasoning as the US Supreme Court in Mahmoud. They could rule that any required teaching about sexual orientation or gender identity violates Canadians’ Charter right to the freedom of conscience and religion. We’re praying that any future legal decisions here in Canada will also preserve the space to teach creational norms around gender and sexuality.

In 2019, a Coptic Christian named Rafael Zaki was expelled from medical school at the University of Manitoba after making provocative anti-abortion statements online. Ever since then, Zaki has been in a protracted legal battle with the University.

Zaki’s case against the University was heard in court last week for a second time. The first time around, the court reversed Zaki’s expulsion for procedural fairness reasons. Then the University expelled him again and he went back to court. ARPA followed last week’s hearing.

Who is Rafael Zaki?

Rafael Zaki is the child of immigrant parents, parents who suffered religious persecution in their home country, Egypt. They immigrated to Canada so their children would have an opportunity for a better life.

Zaki and his family are Coptic Orthodox, a faith that recognizes the sanctity of life.

Zaki did well academically in high school and university. In August of 2018, Zaki was admitted to the Max Rady College of Medicine at the University of Manitoba.

But Zaki was expelled for unprofessional conduct after sharing a provocative 27-page pro-life essay that he wrote on Facebook. His essay contained controversial language and arguments, comparing abortion with other human rights violations such as genocide and slavery.

The University supposedly received multiple complaints from students and faculty, saying Zaki’s posts were disturbing and damaging to the learning environment. The University agreed, characterizing Zaki’s posts as misogynistic, violent, and offensive. Ultimately, the University concluded that Zaki’s conduct violated their professionalism standards.

Initially, Zaki was asked to apologize and undergo a remediation process, but Zaki’s apologies were deemed insufficient. Eventually, the school’s Progress Committee voted to expel him in August 2019 for failing to meet professionalism standards.

Zaki’s First Appeal and Court Hearing

Zaki appealed the Progress Committee decision to the Local Discipline Committee and then up to the University Discipline Committee in July 2020. He lost in both instances. Zaki then applied to court for judicial review of the University Discipline Committee’s decision.

In August 2021, the Manitoba Court of King’s Bench sided with Zaki and quashed the University Discipline Committee decision. The Court found that there was a reasonable apprehension of bias in the disciplinary process. A faculty member had played multiple roles in the investigation and discipline process. The Court also found that the discipline committee failed to consider Zaki’s Charter rights, specifically freedom of expression and religion.

The Court sent the case back to the University to reconsider with an unbiased panel on the discipline committee. The new panel conducted a fresh review of the evidence and expelled Zaki again, who had been re-enrolled in classes for some time already by that point.

The committee acknowledged that Zaki’s Charter rights were engaged but ruled that his expulsion was reasonable anyway. The panel reasoned that medical students are required to meet professionalism standards, and Zaki’s conduct—specifically his social media posts and inability to complete “remediation” to their satisfaction demonstrated Zaki’s lack of understanding of these responsibilities.

The Status of Zaki’s Case

Zaki appealed the Committee’s decision to the Manitoba Court of King’s Bench once again. The hearing took place last week, on March 26 and 27.

In court, Zaki’s lawyer, Lia Milousis, argued that the Committee was biased once again. She emphasized that the University repeatedly shifted their position on what Zaki needed to do to avoid expulsion. For example, Zaki had written multiple apologies because the University implied that doing so would mitigate the consequences. But the University rejected his apologies since they did not recant his core pro-life beliefs, which is what the University staff actually wanted.

Zaki’s lawyer also argued that the University selectively quoted from his essay to make him sound more controversial. Zaki’s factum (written submissions to court) also noted that the Chair of the new discipline panel had a close professional relationship with the Dean. But the Dean was involved in the initial expulsion decision and testified at the second discipline hearing, creating another conflict of interest.

Zaki also argued that the University violated his Charter rights to freedom of expression and religion in a disproportionate way by, in effect, expelling him for not recanting his beliefs.

Zaki hopes the Court will overturn his expulsion soon. If he succeeds, the Court is likely to remit the matter back to the Committee for reconsideration yet again, but it is also open to the Court to find that the University could not reasonably expel him on these facts.

Why Zaki’s Case Matters

Zaki’s case underscores the immense power universities hold over students’ academic and professional futures. It shows how professionalism standards can be abused for ideological and political purposes.

Zaki’s case also raises important questions about protecting freedom of expression and religion in public universities and in regulated professions.

In January 2024, ARPA reported on a B.C. court ruling which concluded that Jehovah’s Witness (JW) elders must turn over certain religious records to the province’s Privacy Commissioner. Those records contained elders’ notes discussing the “disfellowshipping” (similar to excommunication) of two former JW congregants. The elders contended that, as a matter of religious practice, these notes are confidential, kept in a sealed envelope under lock and key, only to be reviewed again by JW elders if a former congregant seeks to be readmitted into the congregation.

However, the former congregants used BC’s Personal Information Protection Act (PIPA) to demand access to the records that relate to them. PIPA governs how organizations of all kinds collect, use, and disclose information about any person. Unlike B.C.’s PIPA, most provinces’ privacy laws do not apply to non-commercial records created by non-profits. PIPA gives a person the right to demand disclosure of information about oneself in the possession of an organization. But that right does not extend to information collected exclusively for personal, artistic, literary, or journalistic purposes.

The Privacy Commissioner ordered the elders to give the documents in question to the Commissioner to determine what, if anything, must be disclosed to the former congregants. The elders appealed to the B.C. Supreme Court, arguing that providing these records to the Commissioner would violate their religious practice. They also argued that PIPA violates the Charter (freedom of religion) and that PIPA should not apply to records created exclusively for religious purposes.

The Court of Appeal found that PIPA does not infringe the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Rather, the Court found that PIPA grants discretion to the Commissioner to order (or not) the disclosure of records and that the Commissioner must consider any Charter rights implicated in its decision. Consequently, any potential Charter infringement results from the Commissioner’s order, not the statute itself. In ARPA’s view, this overlooks the burden that results from having records created for exclusively religious purposes subjected to PIPA compliance and Commissioner oversight in the first place – whether or not the Commissioner issues any orders.

The Court acknowledged that ordering the elders to disclose the records to the Commissioner infringed on their freedom of conscience and religion but also found this was justified. The Court saw it as the only way to advance the “pressing legislative objective” of ensuring people can exercise control over their personal information.

ARPA intervened in this case to highlight the institutional and associational aspects of freedom of religion. We argued that the supposed justification for limiting religious freedom is an ill-defined, non-constitutional personal interest in maintaining control over information about oneself. Lawyers and judges often say that privacy statutes are “quasi-constitutional,” a point that the former congregants’ lawyers raised. ARPA explained that this is because the first privacy statutes in Canada were designed to limit governments’ ability to record personal information and to ensure that people could find out what information the government had recorded about them. It is quite another thing to suggest that finding out what somebody else (e.g. an elder, a journalist, or a friend) has written about you is a quasi-constitutional interest or right. You can read our factum (legal arguments) here.

Unfortunately, the Court of Appeal judgment did not directly address our arguments. In fact, its judgment seems to skip over some of the deeper constitutional issues relating to the proper jurisdiction of the state and the purpose of government oversight of organizational record-keeping. On the positive side, the Court did not stray into making comments or affirming arguments devaluing freedom of religion or denying the distinctiveness of religious organizations. They also did not insist that capturing religious records within privacy legislation is essential (which is a policy choice only B.C. has made).

Rather, the Court simply accepts that PIPA applies to religious records and emphasizes that in the particular facts of this case, it was reasonable to order disclosure of the records to the Commissioner. The Commissioner must then weigh the former congregants’ privacy concerns against the JW elders’ freedom of religion concerns in deciding what information the elders owe the former congregants.

The JW elders must decide within a few weeks whether to attempt to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada. Given that the Privacy Commissioner, lower court, and unanimous Court of Appeal agreed on the outcome, it seems unlikely the Supreme Court will hear an appeal. If the case does not proceed to the Supreme Court of Canada, it will return to the Commissioner to decide what happens next.

Should the Commissioner decide, after reviewing the elders’ notes, that all or part of the information must be disclosed to the former congregants, the elders could appeal that decision to a court. That would be a new case, albeit one with similar constitutional issues.

Last month (and at a prayer breakfast, of all places), Premier Wab Kinew announced that he is considering changing the prayer that opens each day of proceedings at the Manitoba legislature. Currently, at the beginning of every day, the Speaker reads the following prayer:

“O Eternal and Almighty God, from whom all power and wisdom come, we are assembled here before Thee to frame such laws as may tend to the welfare and prosperity of our province.

Grant, O merciful God, we pray Thee, that we may desire only that which is in accordance with Thy will, that we may seek it with wisdom and know it with certainty and accomplish it perfectly.

For the glory and honour of Thy name and for the welfare of all our people. Amen.”

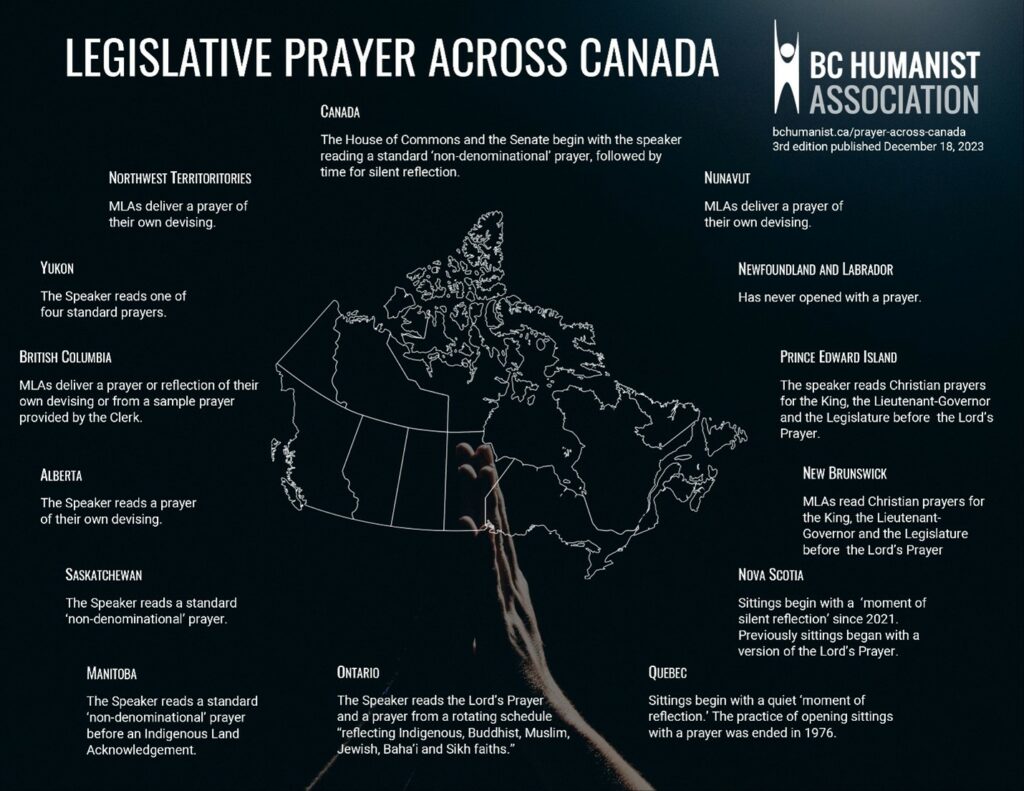

Prayer at the opening of each day at the legislature is a longstanding tradition in the British Parliamentary system, the system of government that Canada’s government is based on. The federal government and almost every provincial government offer such daily prayers. (The BC Humanist Association, very much against the offering of religious prayers in legislatures, has a handy infographic and report of standard practices across the country.)

Despite the longstanding tradition and Canada’s Christian heritage, the premier is considering revising that prayer in light of the growing numbers of Manitobans that don’t identify as Christians. According to the 2021 Census, 54.2% of Manitobans identified as Christian, 36.7% identifying as having no religious affiliation, and 9.0% reporting another religious affiliation such as Muslim, Jewish, Sikh, or Hindu.

“I’m asking faith leaders and people who grapple with the questions of secularism and what does it mean to be a Manitoban today to look at this opening prayer and say, ‘Is there a way that we could spend this minute that more accurately reflects who we are as Manitobans today?’” said Premier Kinew. “Is there a way that we could preserve the space for those who believe in God, and people such as myself who pray every day, but also to be more inclusive — inclusive of different faith traditions, but also inclusive of people who pride secularism in our society, people who may define themselves as atheists or non-believers?”

Abandoning Christian prayers in provincial legislatures is hardly new. In 2008, then Ontario Premier Dalton McGuinty mused about removing the Lord’s Prayer that was offered every session. At the time, MPP Garfield Dunlop, who was on the committee considering whether to remove the Lord’s Prayer, said, “There is a lot more behind it than just the prayer. Our whole British parliamentary system was based on Christianity. That goes right back to the Magna Carta. The first parliamentary sessions held in Great Britain were held in churches . . . Removing one thing is just like chipping away at a foundation. There is no reason to do that.” After a groundswell of opposition to chipping away at that foundation, the Ontario government kept the Lord’s prayer, with even premier McGuinty admitting “that his suggestion to abolish the Lord’s Prayer had resulted in a scolding from his Catholic mother.”

In 2019, the Legislature of British Columbia changed its practice slightly in response to the BC Humanist Association’s letter writing campaign and in opposition to ARPA’s objection to the erosion of British Columbia’s Christian heritage. The province expanded the time for prayer to include “prayers and reflections” and updated the list of sample prayers to remove some overtly Christian language from some prayers and to create new sample prayers from other religions. However, MLAs are still allowed to offer prayer or reflection of their own devising in whatever religious tradition that they wish.

A Christian Argument for Prayer

Reformed Christians should continue to support the manifestation of religious conviction in the public square. We believe in the sovereignty of God over all aspects of creation, including our civil government. He is the one who ultimately controls our provincial government and society, and it is certainly appropriate to call upon His name in the legislature. Prayer recognizes the reality of the presence and power of God.

The practice of prayer within the legislature recognizes the importance of the public manifestation of personal religious convictions. True faith is more than just a personal relationship with God. It also applies this faith to all activities, including the realm of politics and public service. While many people and organizations may seek to contain faith and religion exclusively in the private sphere, it is impossible for those grafted into Christ not to exhibit public fruits of faith. This public manifestation of faith includes voting based on biblical truths, treating others respectfully as image-bearers of God, and recognizing God’s authority over all things in public prayer.

The preamble of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, lyrics in our national anthem, and the inscriptions on the national parliament buildings reference Canada’s Christian heritage. Any attempt to relegate prayer to private settings is an attempt to further erase the religious heritage of our country and provinces.

An Opportunity for Action

Despite Premier Kinew’s personal suggestion that the prayer in the legislature be changed, he is seeking the input of Manitobans on how prayer is offered in the legislature. A government news release last month states the following:

“The Manitoba government is seeking input as it works to refresh the prayer read by the Speaker at the opening of each legislative session, Premier Wab Kinew announced this morning at the ninth annual Multi-Faith Leadership Breakfast.

‘Every day that the legislature is in session, we begin with a prayer – and that prayer has gone unchanged for many years,’ said Kinew. ‘We believe it’s time to update this opening to ensure it captures who we are as Manitobans today. There is space within the words we share each day for more Manitobans to feel grounded and to pause for reflection. That’s why I’m inviting Manitobans from all walks of life to work with us to ensure that who we are as Manitobans, as one Manitoba, is reflected.’

To ensure the legislature opening remains relevant to Manitobans from all walks of life and reflects the values and priorities of Manitobans, the Manitoba government will host a roundtable to gather perspectives on changes to the legislature opening.”

If the premier is soliciting input, let’s give it to him! Send an EasyMail to the premier and your local MLA today.

P.S. If you don’t think that it is appropriate for the Speaker to offer a Christian prayer in the legislature, reach out to us at [email protected]. We’d be interested in having a discussion!

The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta has proposed changes to its policy on conscientious objection by requiring all doctors to provide “effective referrals”.

The College licenses and regulates doctors in the province. It has the power to investigate and discipline any doctors who do not follow the College’s policies.

Albertans can share their views on this proposed change until January 15. This is an opportunity to stand up for ethical, conscientious doctors. We offer some advice on how to do so at the end of this article.

Proposed ‘Conscientious Objection’ Policy

The College’s proposed policy would require doctors to clearly state their conscientious objection, to provide accurate information about available services, and to continue providing care for a patient as long as required. But it would also require doctors to “proactively maintain an effective referral plan for the frequently requested services they are unwilling to provide.” Similarly, it requires members not to “expose patients to adverse clinical outcomes due to a delayed effective referral.” In other words, although the policy does not require doctors to provide objectionable services (such as abortion or physician-assisted death), it requires them to facilitate a patient’s timely access to such services.

Effective Referral

Currently, only Ontario and Nova Scotia explicitly require an effective referral, with Alberta set to become the third if this policy is adopted. While the CPSA does not define ‘effective referral,’ others have defined it as “Taking positive action to ensure the patient is connected to a non-objecting, available, and accessible physician, other health-care professional, or agency.” Essentially, an ‘effective referral’ requirement ensures that a doctor facilitates euthanasia or abortion by connecting a patient with a doctor or resource that will help the patient receive the requested service. Effective referral policies violate doctors’ consciences and undermine our healthcare system. You can read more about effective referral and why it is a concern here.

Participate in the Consultation

Any Albertan can provide feedback directly to the College. There are two ways to do so. First, you can fill in a comment box on the College’s website and select whether to make your comment public or not. Second, you can fill out a brief survey, consisting of 14 questions – just be aware that the survey touches various aspects of the proposed policy besides effective referral. Choose the option that is best for you and share your thoughts by January 15, 2024.

Suggested Talking Points

Here are some talking points that you can use to help form a response to the consultation.

- Freedom of conscience and religion are fundamental freedoms under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

- Doctors should be permitted to pursue their profession without violating their conscience.

- While there is no requirement in Alberta for physicians to administer MAiD or other controversial services, many doctors object to participating in the process through an effective referral because they see it as participation in the procedure.

- Most provincial medical regulatory bodies do not require effective referrals for issues of conscience.

- Doctors’ conscience rights also matter for patients.

- Limiting conscience rights will limit the number of conscientious objectors who enter or remain in the medical field and reduce access to health care. In Ontario, doctors have been leaving the profession, moving out of the province, or retiring from their careers due to effective referral requirements.

- Patients should be able to choose a doctor they can trust to make ethical decisions. For example, many patients want a doctor who will never offer them MAiD, particularly in a society where MAiD is often easier to access than care.

- The medical profession is strengthened through diversity of thought and diversity of doctors.

- Doctors should be able to provide the best possible medical advice, whether or not the patient disagrees with that advice.

- In other medical situations, such as requests for dramatic liposuction or a tongue splitting, doctors are permitted to deny the patient’s request without fear of discipline from the College.

- Forcing a doctor to do something that they believe is not in the best interest of the patient muzzles a doctor from giving an honest medical opinion.

- The number of Albertans dying through MAiD has been steadily increasing. As MAiD may extend to those with mental illness by March 17, 2024, more doctors are concerned about even more patients being eligible for MAiD. As a recent brief by the Society of Canadian Psychiatry noted, most psychiatrists oppose expanding MAiD to mental illness, despite not being conscientious objectors to MAiD in general.

Once again, please send your thoughts to the College by January 15, 2024. We encourage you to use the ideas in this article, expand on them, and present them in your own words.

**Update**

As of January 11, 2024, the College has updated its consultation page with the following:

“Based on initial feedback received, the term ‘effective referral’ will be removed from the Conscientious Objection standard. Those that provide feedback during the consultation period will be consulted again during the re-consultation phase and see additional edits before final approval.”

While we have yet to see what a revised policy looks like, the decision to remove the term ‘effective referral’ is a promising development for which we can be thankful. We encourage you to still weigh in on the proposed policy, and also support the College in their decision to remove the term ‘effective referral.’

In recent weeks, the story of one terminal cancer patient who had to be transferred out of Providence Health so that she could be euthanized was reported on by various news outlets. These stories prompted Health Minister Adrian Dix to promise that he would talk to Providence Health and pressure them to provide euthanasia on site.

Providence Health, “inspired by the healing ministry of Jesus Christ… is a Catholic health care community dedicated to meeting the physical, emotional, social and spiritual needs of those served through compassionate care, teaching and research,” according to its mission statement. For the past decades, denominational health care providers have operated through a master agreement between the province and the denominational health care facilities association. This agreement allows religious health care providers to partner with the provincial government but still retain “the right to determine in the context of their respective values and traditions the mission and values of the owner so as to preserve the spiritual nature of the facility.”

In other words, this agreement allowed religious health care providers like Providence Health to opt out of providing things they thought were immoral, such as abortion, contraception, or euthanasia.

But now the provincial government is under pressure to scrap or renegotiate this agreement. This would lead to the province either defunding Providence Health and possibly taking over their facilities (as happened already with Delta Hospice) or forcing Providence Health to provide euthanasia against their ethical, conscientious, and religious convictions. Unlike Delta Hospice, Providence Health is a big player in health care in Vancouver. It operates ten different institutions in Vancouver and is in the midst of building a brand new, 548-bed St. Paul’s Hospital at a cost of $2.1 billion in partnership with the provincial government.

In his promise to pressure Providence Health into providing euthanasia, Minister Dix ignores two key pieces of history and an important legal reality.

First of all, the government is relatively new to delivering health care. Until the late twentieth century, churches and civil society shouldered the bulk of the duty to care for the sick and dying. In many cases, this health care came at great personal cost. Governments were absent.

One ancient example is the Justinian Plague, during the dying days of the Roman Empire, when most citizens in Rome hid indoors to avoid catching the plague, leaving the sick and dying to fend for themselves. The exception was the Christians, who took it upon themselves to care for those infected by the plague to either help them recover or to comfort them during their last days. The Roman Emperor Julian, although an opponent to the Christian faith, nevertheless marvelled that they “care not only for their own poor but for ours as well; while those who belong to us look in vain for the help that we should render them.”

A more recent example is Mother Theresa, a devout Catholic from Macedonia who moved to India to minister to the sick and needy. Her compassion and mission to live out her faith in service to the sick have inspired countless others.

When it comes to health care, the primary role of governments has been to ensure that every person has the financial means to obtain health care, not to dictate how the sick are cared for. The main objective of Canadian health care policy, set out by the Canada Health Act, “is to protect, promote and restore the physical and mental well-being of residents of Canada and to facilitate reasonable access to health services without financial or other barriers.” It accomplishes this objective by making the government the single payer for all medically necessary services. Governments should amplify rather than supplant religiously motivated efforts to care for the sick.

This was precisely why BC’s Denominational Health Care Facilities Association agreement was struck in 1995. Its purpose was to further the partnership between the provincial government (as the single payer for health care) and religious organizations (as one of many providers of health care) to care for the sick and dying. Scrapping the agreement or forcing religious institutions to violate their moral principles is equivalent to saying to the oldest player in health care, “Thank you for your service; now beat it.”

Which brings us to the second lesson from history. For thousands of years, health care practitioners have followed the Hippocratic oath. That oath includes the promise to use “regimens which will benefit my patients according to my greatest ability and judgment, and I will do no harm or injustice to them. Neither will I administer a poison to anybody when asked to do so, nor will I suggest such a course.” Patients could be confident that a physician was seeking to preserve their life and restore their health. Euthanasia was anathema.

This ethical standard was reflected in the Canadian Criminal Code, which outlawed euthanasia, assisted suicide, as well as counselling or encouraging someone to end their life. Euthanasia and assisted suicide were serious crimes.

Unfortunately, that changed when the Supreme Court and Parliament jointly legalized what they euphemistically called Medical Assistance in Dying. Over two thousand years of devotion to preserving the health of patients and doing no harm was thrown out the window.

Yes, euthanasia is now legal in Canada. That does not mean that every health care professional or institution, even if partially funded by the government, is obligated to provide euthanasia. Legal does not mean obligatory. There may be very good reasons why we don’t allow care aids to administer euthanasia and why not every small-town hospital in BC provides open heart surgery. By way of analogy, the legalization of marijuana does not mean that governments are obligated to provide everyone with the substance or force other institutions to provide it.

It is absurd that any institution should be criminally investigated, as Providence Health was, for not doing something that was a serious crime only 7 years ago, namely killing someone at her request.

Providence Health also has the constitution on its side. The Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees freedom of conscience and religion (which protects individual health care practitioners from being forced to provide euthanasia against their religious or conscientious convictions), but also freedom of association. Taken together, these freedoms protect a religious health care institution’s choice to refuse to engage in a practice for religious and moral reasons.

When Dr. George Carson, an obstetrician and gynecologist in Saskatchewan quoted in an article by Daphne Bramham, says that “conscientious objection for a building — particularly one supported by taxpayers — makes no sense,” he fundamentally mistakes what an association is. Providence Health isn’t a building. Providence Health is a collection of health care professionals and support staff who have freely associated together to serve a common cause: “inspired by the healing ministry of Jesus Christ, Providence Health Care is a Catholic health care community dedicated to meeting the physical, emotional, social and spiritual needs of those served through compassionate care, teaching and research.”

Providence Health operates 20 of 68 palliative care beds in the Coast Health region and is in the middle of constructing, in partnership with the provincial government, a new and expanded St. Paul’s Hospital. In a province that is in dire need of more palliative care beds (and more health care capacity in general), the Premier and the Health Minister shouldn’t be picking ideological battles with religious health care providers. Instead, to better serve its citizens, the government should be asking: how can we form more, new, and better partnerships with faith-based institutions to provide the services that British Columbians need?

So… could you spare five minutes of your time to send your MLA and Minister Dix a note, voicing your support for Providence Health’s right to operate according to their religious convictions?

On March 1, 2022, MPP Sam Oosterhoff introduced Bill 89, Protecting Ontario’s Religious Diversity Act, 2022. This important private member’s bill will help protect religious freedom in Ontario by adding “religious expression” as a separate ground of protection in the Ontario Human Rights Code. It’s exciting to see important legislation like this being introduced by individual MPPs in Ontario.

Background on the Human Rights Code

The Ontario Human Rights Code has been law since 1962. It initially protected against discrimination on the basis of race, creed, colour, nationality, ancestry, and place of origin. Since then, this list of six has been expanded to include 14 “protected grounds.” The Code now prohibits discrimination based on these criteria: 1. Age, 2. Ancestry, colour, or race, 3. Citizenship, 4. Ethnic origin, 5. Place of origin, 6. Creed, 7. Disability, 8. Family status, 9. Marital status, 10. Gender identity or gender expression, 11. Receipt of public assistance in housing, 12. Record of offences in employment, 13. Sex, 14. Sexual orientation.

The 14 criteria are protected in five different areas of society: 1. Housing, 2. Contracts, 3. Employment, 4. Goods, services, and facilities, and 5. Membership in unions, trade, or professional associations.

The Human Rights Code prohibits discrimination between citizens, or discrimination by government, based on specific identifying factors and in specific areas of daily life. (It is different than the Charter of Rights and Freedoms which is supposed to shield citizens from the government itself). There are plenty of concerns we could raise with the Human Rights Code overall and how it is applied, including discussions on whether it is effective or abused. However, those concerns aside, Bill 89 (2022) is an important and helpful improvement to the Code.

What Does Bill 89 (2022) Do?

Currently, the Human Rights Code protects against discrimination based on someone’s ‘creed.’ This means that every Ontarian should have access to the same benefits and opportunities regardless of their creed. The problem is that ‘creed’ is not defined in the Code (though the Ontario Human Rights Commission has published this paper on “creed.”

In past court decisions, the courts often refer to religious beliefs and practices related to creed, also including non-religious belief systems. The Ontario Human Rights Commission clarifies that creed can include a belief system that is deeply held, linked to someone’s identity, comprehensive, addresses ultimate questions about human life and existence, and has a connection to a community sharing that belief system.

It’s still somewhat vague, but creed is roughly related to religious freedom. What Bill 89 (2022) does is amend the Ontario Human Rights Code to explicitly protect Ontarians against discrimination because of religious expression in addition to creed. Ultimately, it adds needed clarity to the protected grounds in the Human Rights Code, to expand on the importance of religious freedom.

Adding religious expression to the Code in this way protects the ability for Ontarians to live according to their beliefs. Every Ontarian must be able to speak about and live according to their religious beliefs. Religious freedom does not only mean the ability to hold certain beliefs internally or in isolation but also to act in a way that is consistent with those beliefs.

What Can We Expect if This Bill Passes?

If this bill passes, it is hard to say what kind of change it will make in practice, as the Code is applied by the Human Rights Commission and/or the Human Rights Tribunal. The Ontario Human Rights Commission and the Tribunal tend towards prioritizing other protected grounds over creed. There is often a misunderstanding of what religion is, and what it implies for the way people act.

As Christians, our faith impacts everything we do, including the ways we treat things like employment or the provision of goods and services. We seek to act in a way that is connected to our faith and to uphold human dignity and human rights. This bill is a step in the right direction toward further protecting religious liberty and the ability to act according to one’s beliefs, including in interactions with other Ontarians.

The bill is not likely to pass primarily because of its timeline. The Ontario provincial election is set for June 2, 2022, and the legislature will stop their work in advance of that for the campaign period. Private members’ bills often take time to go through the process of debate, votes, and committee study, so there is likely not enough time for that process to be completed. However, the bill is scheduled to be debated at 2nd reading on March 29, and is worth supporting when that happens, even if it does not have time to become law.

Conclusion

We care about religious freedom and religious expression, not just for Christians, but for everyone. Religious freedom is a fundamental freedom that is critical to allowing a society like ours to flourish. To be human is to be religious and includes the ability to express one’s religion. Bill 89 (2022) supports principles of religious freedom and human liberty and seeks to provide further liberty for Ontarians to live according to their faith.

Religious freedom requires vigorous defence by our civil governments, and Bill 89 (2022) seeks to improve that defence in Ontario. Stay tuned for further ways you can support this bill when it is debated at 2nd reading.

The Ontario Superior Court of Justice is the third Canadian court to uphold the constitutionality of severe restrictions on assembled worship services. ARPA Canada has had the privilege of intervening in each of the three cases (the other two being in British Columbia and Manitoba). While we are disappointed in the result from the court, this latest decision shows an acceptance of one of ARPA’s key legal arguments.

Quick Recap of the BC & Manitoba Cases

The first case was heard in British Columbia in March of 2021 after churches had been completed prohibited from gathering since the previous November (even though almost all other sectors were still open, including restaurants and pubs, museums and schools, gyms and swimming pools, business gatherings and movie sets, and more). A few churches had received tickets for gathering. British Columbia’s Chief Justice Hinkson took less than two weeks after the hearing to issue a decision in which he emphasized deference to the Provincial Health Officer and upheld her orders.

The second case was heard in May of 2021 and Manitoba’s Chief Justice Joyal took five months to write his decision. This case did not just focus on restrictions on worship services but involved thousands of pages of evidence relating to the risk of Covid-19 and different approaches to mitigating risk. As in BC, Justice Joyal focused on the deference he felt was owed to the government despite the infringement of the Charter protected freedoms of religion, expression, and assembly.

ARPA’s Arguments

ARPA’s arguments in each of the provinces have been similar. Focusing on our most recent submission, ARPA Canada made three constitutional arguments:

- That Canada’s constitution and jurisprudence emphasize the existence of and legitimacy of authorities other than the civil government. For example, the Supreme Court of Canada affirmed this institutional pluralism in a case called Reference re Secession of Quebec where they said our “constitution may seek to ensure that vulnerable minority groups are endowed with the institutions and rights necessary to maintain and promote their identities.” These institutions need protection and are owed deference in certain matters.

- That the court ought to weigh the cumulative impingement of the various fundamental freedoms at issue in this case – including freedom of religion, freedom of expression, freedom of peaceful assembly, and freedom of association. It is these compound Charter violations that need to be justified by the government.

- Finally, part of the government’s duty to justify the impingement on Charter freedoms includes demonstrating that they chose measures from a range of reasonable alternatives. We argued that a range of reasonable alternatives may include percentage capacity limits. For example, a 25% and a 50% limit may both fall on the range of reasonable alternatives. But a total prohibition is something else entirely and fails this test.

The Results in Ontario

Justice Pomerance found that while the restrictions on gathered worship did violate the Charter’s guarantee of freedom of religion, the government was able to justify it. The fact that this court upheld not only total prohibitions of in-door gatherings but also of outdoor gatherings is especially concerning to us in a seeming rejection of our third argument. Justice Pomerance also rejected our compound Charter violations argument, but with the silver lining that in considering freedom of religion (the only freedom she did a full analysis of) she spent time talking about religious expression (especially singing) and the importance of religious assemblies as a part of that freedom.

A Recognition of the Role of the Church

Where we see the most encouragement is the Court’s interaction with our institutional pluralism argument. Right at the beginning in her preliminary observations, Justice Pomerance lists deference to religious claimants directly after listing deference to the state. In discussing the Charter’s protection of freedom of religion she states that it “contemplates the co-existence of spiritual and civil authority” (para 85) and continues: “The state does not hold a monopoly on helping people cope with the stress of a pandemic. Religious institutions are well equipped to offer non-medical, psychological, and spiritual guidance. Institutional pluralism recognizes the complementary roles assumed by the church and state and calls for mutual respect between their sphere of authority” (para 87).

You can even see the language of sphere sovereignty come out in that quote. She goes on to cite the BC decision’s findings of religious bodies’ sphere of independent authority concluding: “It is that authority that was constrained by religious gathering limits” (para 106). That is, not only is she recognizing that churches have authority, but that this authority was constrained by Covid-19 restrictions.

Nevertheless, the Court finds the Government Limits were Justified

Of the three cases so far, Justice Pomerance gives the most fulsome explanation of the cost that Covid-19 restrictions have on churches as an institution. But she still finds the cost was justified. Much of this comes down to how serious she views the government’s enterprise as she describes, “The government objectives in this case are amongst the most compelling imaginable – the protection of human life in the face of an unprecedented and unpredictable virus, carrying a threat of devastating health consequences” (para 159).

This sounds reasonable on its face, but the problem is that our government is supposed to also have the objective of preserving our fundamental freedoms. Yet that consideration was seemingly lacking from the Ontario government’s response. Justice Pomerance lists the factors that the government of Ontario did consider as they passed restrictions. This is the list the government put in evidence:

- Limiting the transmission of Covid-19;

- Avoiding closures while reducing the risk of transmission;

- Keeping schools and childcare facilities open;

- Maintaining health care and public health system capacity;

- Protecting vulnerable populations; and

- Providing additional support to those disproportionately affected by the pandemic (para 32).

What’s missing from this list is the protection of the fundamental freedoms especially freedom of religion and the public worship of our God. Why is keeping schools open being held in higher regard than allowing religious adherents to live out their religious obligations? And a full embrace of institutional pluralism would have recognized that when it comes to providing support to those affected by the pandemic, the government ought to rely on churches to care for the spiritual needs of Ontarians rather than preventing them from fulfilling their role in our society. As Dr. Schabas said in his evidence before the court, “The fear generated by public health messaging makes religion even more important to the health of believers. Promoting fear and then denying people their means of dealing with fear compounds the harm.” Churches were severely limited in their ability to minister to the spiritual needs of the people surrounding them. In trying to accomplish their objective, the government declined to consider working with what could have been a strong ally.

Conclusion

We’re disappointed with the result of this case – especially that the total prohibitions of even outdoor worship were upheld as constitutional. But these cases aren’t finished yet. The BC appeal is being heard later this month and ARPA Canada will again have the privilege of presenting arguments. We intend to continue to provide the Biblical perspective grounded in Reformed theology about the importance of the role of the church and the government’s duty to respect it even in the midst of responding to a pandemic.

By Tabitha Ewert and Levi Minderhoud

What is religion? What are the marks of religious adherence? How far should the civil government go in recognizing, respecting, and legitimizing new and distinct religions? These are questions that a Quebec court recently had to wrestle with.

In the case of Institute of Taoism Fung Loy Kok v. City of Montreal, an organization that offered tai chi classes had applied for an exemption from property taxes claiming that it was a religious institution. (Tai chi is a series of gentle physical exercises and stretches that has a meditative element to it.) Both the Institute and the city of Montreal brought witnesses to the court hearing to speak on the nature of tai chi and the history of the Taoist religion. While the specific question in this case – whether Taoist tai chi is a religious practice or just another form of physical exercise – might not affect Christians, the larger question pondered in the case – what is religion? – is a question that any Christian should take note of.

It is rare that a court considers the nature of religion and what it means to be religious. Justices hearing freedom of religion cases rarely spend any time on this deeper question because the bar is very low to establish an infringement of freedom of religion. Generally, all the court is looking for is whether the claimant has a sincerely held religious belief that has been interfered with. If so, an infringement of freedom of religion is recognized. The real work in these cases happens in the next stage: whether the government can justify the interference under section 1 of the Charter (you can read more about the section 1 analysis here).

This Taoist tai chi case, though, is not a Charter case. It is a tax law case. The city of Montreal waives property taxes for religious institutions if the property is not being used “with a view to income but in the immediate pursuit of its constituent objects of a religious or charitable nature.” Most other cities across Canada have similar tax-exemption policies for religious institutions. The main question in the case is clear: are the pursuits of this Institute (which mainly uses the building to practice tai chi) religious? And beyond this question, how might this case impact the state’s recognition of the Christian religion, or even the religion of secularism, in the future?

What is a religion?

The court identifies some core elements of a religion, “including:

a) a conception of the world based on the supernatural in a perspective of salvation and establishing the place of the human in the cosmos,

b) a moral code in the form of precepts and rules of conduct, and

c) worship which integrates assemblies, ceremonies and rites of transition (128).”

The court recognizes the challenge of evaluating an eastern religion in a western culture with a western idea of religion (largely based on Christian beliefs). Nevertheless, the court does identify core teachings of the Institute as “doing good deeds and serving the community, the practice of ritual and ceremonies, [and] the practice of physical activity, namely Taoist Tai chi.” The court notes that there is a “belief in the vital, eternal and timeless force that is Ch’i (Qi) and in the journey to associate with it [that] is shared by all Taoist communities regardless of their obedience.”

The communal aspect of religion

The main hurdle in this case is whether the religious character of Taoist tai chi involves a shared or collective belief. Individuals may hold religious beliefs, but for something to be a religion requires a broader community, particularly if an institution or organization, rather than an individual, is asking the state to recognize its religious nature. The reality is that many of those who practice tai chi are not adherents to the religious beliefs that the Institute holds. In fact, a Canadian census found that in Quebec only 280 people identified Taoism as their religion, but the Institute estimates the number of their members as 2,000. While this fact is eye-catching, the court says this does not defeat the case but draws an analogy to famous cathedrals, mosques, or temples around the world. Many tourists who do not adhere to the beliefs of the institutions visit these sites, yet these sites “remain places devoted to the beliefs, rituals and means of expression specific to the religions which presided over their foundation even if the number of visitors exceeds that of the members of each of the transmission communities.”

The court also considered whether the Institute was acting in bad faith, trying to claim a religious property tax exemption for their primarily non-religious activities. In other words, was this a gimmick to try to lower the expenses and increase the profits of the Institute? This is an important question for the court to consider; if religious recognition is given to organizations too easily, anyone might claim that a particular activity is religious or try to establish their own religion to gain special tax privileges. In this case, the court finds that the Institute is not operating with a view to make income but to genuinely further their religious beliefs.

In the end, the Institute won its case, and the property tax exemption is granted.

The Impact of this Case

While we have little at stake in whether this Institute is granted a religious tax exemption, the commentary about what defines a religion is quite fascinating and applicable to how Christians may engage in the public square. In a culture that increasingly treats religious beliefs as primarily individual and private, the emphasis on the communal aspect of religion is encouraging. This is an essential part of our own faith, as the Nova Scotia court in the Trinity Western University case explained well:

[Evangelical Christians’] religious faith governs every aspect of their lives. When they study law, whether at a Christian law school or elsewhere, they are studying law first as Christians. Part of their religious faith involves being in the company of other Christians, not only for the purpose of worship. They gain spiritual strength from communing in that way. They seek out opportunities to do that. Being part of institutions that are defined as Christian in character is not an insignificant part of who they are.

It is also encouraging to see the court in this case recognize how broad religious activities are. In a world that often views religion as a pietistic affair of prayer and churchgoing, it is good that the courts recognize that religion can also impact our practical day-to-day lives. If a form of exercise – tai chi – can be recognized as an overtly religious activity, other activities commanded by God – visiting widows and orphans, giving to the poor, or educating children – may also (continue to) be recognized as religious activities as well.

Tabitha Ewert is the legal council for ARPA and Levi Minderhoud is the BC Manager for ARPA

On Friday, May 21, 2021, the Supreme Court of Canada released their decision in Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church et al. v. Aga et al. The unanimous decision is a resounding victory for the authority and autonomy of the church over questions of doctrine and membership. Thank the Lord for this positive development!

This case was appealed to the Supreme Court after the Ontario Court of Appeal ruled unanimously that the civil courts could adjudicate a dispute between several former members* and the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church regarding their membership status and other matters.

The controversy that gave rise to this case had to do with a theological movement within the church that some members considered heretical. The plaintiffs in this case had participated in a church committee established to investigate this heretical movement and made recommendations to church leaders regarding what to do about it. The church leaders only followed the committee’s recommendations in part. The plaintiffs allegedly continued to agitate for more steps to be taken against the alleged heretics. In the church leaders’ view, the plaintiffs were causing further division and strife. Eventually, their memberships in this particular church (but not the larger denomination) were suspended. It was considered by the church to be a disciplinary step. The church also issued a trespass notice to them, telling them not to attend a specific cathedral until they reconciled with the church.

The members sued their church. They asked the lower court to order the church to reinstate them as members and even asked the secular court to compel the church to take certain steps to implement the committee’s recommendations, including censuring other church members for (alleged) heresy.

The Supreme Court hearing and decision

The church made several important arguments at the Supreme Court. First, because there were no property rights or other recognized legal rights (like property, employment, or contract rights) attached to the plaintiffs’ membership in the church, there was no legal basis for taking the church to court. The court agreed, noting that “Jurisdiction to intervene in the affairs of a voluntary association depends on the existence of a legal right which the court is asked to vindicate.” (para. 3, 27-32). Second, the issues raised by the case were not appropriate for a civil court to adjudicate, since they involved questions of interpreting and applying the Bible and religious teaching. Third, the remedies sought by the plaintiffs were not appropriate for a civil court to order and would interfere with the Church’s freedom to govern itself as a religious body.

The Court ended up disposing of the case with a particular focus on the question of contracts. The disgruntled members had argued (and the Ontario Court of Appeal had supported this idea) that the bylaws and constitution of the church (similar to a Reformed Church Order) was a legal document, and that membership in the church was a contractual relationship. Since contracts are reviewable by courts, the argument went, the membership in this church and expulsion from it was reviewable. The Supreme Court soundly rejected this argument. They wrote, “In the religious context, even the use of concepts such as authority and duty need not reflect an intention to create legal relations: the parties may be speaking of religious obligations rather than legal ones.” (para. 41). The Court also stated, “More importantly, becoming a member of a religious voluntary association – and even agreeing to be bound by certain rules in that religious voluntary association – does not, without more, evince an objective intention to enter into a legal contract enforceable by the courts.” (para. 52).

ARPA Canada’s intervention

ARPA Canada intervened in this case to provide a Reformed perspective on the relationship between and the limits of the government’s civil jurisdiction and the Church’s spiritual jurisdiction. ARPA argued that a civil matter must be raised in order for a civil court to hear a case. The plaintiffs’ lawyer argued that ecclesiastical rules for discipline and other governance matters would be pointless if they were unenforceable in civil court. ARPA argued in reply that church teaching and rules for discipline and other matters do not need the backing of civil power to be meaningful or effective. As Calvin wrote, “church discipline requires neither violence nor physical force, but is contented with the might of the word of God.”

The Supreme Court was obviously engaged with ARPA Canada’s argument; they even cited ARPA specifically, writing, “courts should not be too quick to characterize religious commitments as legally binding in the first place (as the intervener the Association for Reformed Political Action (ARPA) Canada observed).” (at para. 42).

Implications of the ruling

This ruling is a wonderful restatement of the independent jurisdiction of the church over matters of church discipline (membership in the church) and doctrine (and how to deal with alleged heresy). For this we can be very thankful. However, there are hints in this decision that churches that incorporate might be subject to secular court review in the matter of a dispute between members and their elders. Reformed churches, in particular, must be cautious when it comes to the question of incorporation. When a church incorporates, it agrees to follow certain statutory rules, which grant certain legal rights to their members. This could result in a flipped relationship between elders and members, where members can exercise veto power over elder decisions. This would be contrary to Reformed ecclesiology. We recommend that any new Reformed church that may be instituted, or any current Reformed church that is incorporated, consult with a Christian lawyer who understands Reformed ecclesiology to ensure that any legal arrangements are done to minimize the potential for secular court review of elder decisions. Contact us at [email protected] to discuss further.

For further reading:

You can read the Supreme Court’s Aga decision for yourself.

You can also watch the video recording of the hearing – John Sikkema makes arguments for ARPA at the 56:30 mark.

You can read ARPA’s written submissions to the court.

For more background on this case, see our first article on the Aga case and the important issues it raises.

For further exploration of the relationship between church and state when it comes to church discipline, see our essay “Who Holds the Keys to the Kingdom Of Heaven?” That essay is the first of a series. Part 2 is “Scripture, Not State Law, Instructs How to Do Church Discipline.” Part 3 is “Handing Over the Keys? The Challenge of Church as Legal Entity”.

*Note: although the Church in this case had formed a corporation to hold church property, the church members were not corporation members.