What is ‘Just Desert’ for Drug Use?

As discussed in the first article of this series, there are a few different approaches governments might use to respond to the drug crisis. Until recently, Canadian jurisdictions have focused on combatting drug use through criminalization and incarceration. However, in the past few years, our governments have realized that approach has been relatively ineffective and are instead trying different responses. Instead of incarceration and safe supply, Canadian governments should be focused on treatment and recovery. I will examine each of these options in turn, closing with ideas for a way forward.

‘Safe Supply’

The federal government should not provide exemptions for safe supply, decriminalization, or safe injection sites. Safe supply and thereby government endorsement of drug use is dangerous and problematic. The only use for publicly funded drugs should be during treatment to manage symptoms of withdrawal and help addicts get clean. In contrast to the ‘safe supply’ approach pursued by the BC government and others, a group of researchers at Simon Fraser University chose instead to call safe supply ‘Public Supply of Addictive Drugs,’ to avoid the implication that these drugs are safe for consumption. This group concludes that Public Supply of Addictive Drugs “represents a human experiment that conflicts with the ethical principles of physicians, clinical psychologists and other regulated health professionals.”[1]

There are two main problems with safe supply. One is the implication that these drugs are safe. They are unsafe even though they may be safer than some alternatives. In 2023, BC permitted doctors to prescribe ‘safer supply’ fentanyl, a drug that is at least 10 times stronger than hydromorphone, which is typically used for safe supply. Of particular concern, the existing protocols do not require parental consent if minors access fentanyl through safe supply.[2] Additionally, some of the impacts on public safety may be a result of safe supply and safe injection sites. For example, in Ontario, calls for provincial review of safe injection sites have increased since a woman was killed near a site in Toronto.[3] Others have noted increased theft rates around safe injection sites to fund drug addiction.[4]

Second, journalist Adam Zivo found that “safe supply” may also be fueling a different kind of opioid crisis. Safe supply drugs still give a high, but not as much of a high as stronger drugs. Drug users near safe supply programs will often take the safe supply drugs and sell them in the community to help them afford stronger drugs. Hydromorphone is the drug typically used in safe supply, and street prices for hydromorphone have decreased considerably, particularly as one gets closer to a safe supply site.[5] This seems to have extended to the point where safe supply drugs are the new popular drug in high schools and have reportedly been the cause of overdoses in teenagers.[6] Some will distinguish between safe supply and supervised injection sites, where addicts are required to consume drugs under supervision, and the drugs cannot be sold in the community. This mitigates concerns about drugs ending up in the community but concerns about public endorsement and provision of drugs remain.

The safe supply approach leans towards treating drug addiction as solely a health care problem, leaving no room for moral agency and responsibility. It treats addicts as mere victims of their circumstances and does not encourage them to change.

Incarceration

While the drug crisis cannot be treated solely as a health care problem, it also must not be treated solely as a criminal problem. No jail time should be required for drug possession or use, except as a last resort. Mandatory jail time can result in people being incarcerated for drug possession or drug-related offenses when those offenders could be dealt with more appropriately through an alternative sentence. Convictions for petty crimes tend to fill our prisons with people who are not dangerous and do not need to be separated from their community through incarceration. Alternative sentences can prevent anti-social associations and promote good behaviour.[7]

Ultimately, the goal of the justice system should be to enact both just punishment and restoration, to work towards peace and harmony within communities.[8] Jail time does not incorporate restoration back into the community and can make the problem worse for drug addicts. Jail time could also put addicts at an increased risk of overdose. If drug users go to jail, they lose their tolerance for drugs over time. They generally don’t receive the proper supports to get clean while in jail, so they go back to drugs when they are released. Since they have lost their tolerance while in prison, they might go back to the dosage of drugs they used to take and end up overdosing.[9] Even if there are drug treatment programs within prison, there is a lack of help for people to be reintegrated into their communities upon release, making it easy to return to drugs. And many prisoners still have access to drugs while in prison. Some correctional facilities have even incorporated safe injection sites into their facilities.[10]

People with criminal records face multiple barriers to employment, housing, and other areas necessary for reintegration and change.[11] Giving a drug user a criminal record makes it harder for them to live an honest and clean life down the road and generally does not help them get off drugs. Prisons should be reserved for removing dangerous offenders from society. Incarceration should remain an option for those who produce and traffic drugs. And of course, other crimes committed due to drug addiction should be fully prosecuted under the criminal law. Drug use and possession, however, are not dangerous offences that require a person’s removal from society.

Nonetheless, the use and possession of hard drugs should remain illegal under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. Treatment programs should be offered by a variety of community organizations, in collaboration with the Ministries of Justice and Health, that have proven effectiveness in combatting drug addiction. The effectiveness of these programs should regularly be reviewed. Such programs should not solely focus on getting a person off drugs but should also seek to provide support in re-entering the community without the need to return to drugs.

Treatment and Recovery

While addicts may want to get clean, treatment is not always an appealing option while they are addicted. Some drug addicts need drugs to help with withdrawal and to ease them off addiction. Any drugs that are provided should be done under supervision, ensuring that drug use is monitored and users are pushed towards treatment programs. Risk of arrest in itself might push someone into a treatment program. For example, one of the key advisors on Alberta’s drug addiction approach, a former drug addict, noted that the ultimatum of treatment or jail saved his life.[12]

Canadian drug policy should not simply focus on drug overdose and death, but also on the broader range of harms that drug use causes, providing opportunity to overcome addiction. Drug users must be encouraged to change, if necessary through somewhat coercive measures. Canada should incorporate a multidisciplinary drug court or dissuasion commission which presents (and enforces) treatment options as alternatives to incarceration. In the case of simple drug use or possession, the court or commission may choose to make the person pay a fine. In the case of more regular use or addiction, the court or commission may push the person into treatment. Canada must not rely solely on voluntary treatment programs to solve the drug crisis. One author writes, “A voluntary drug treatment program works about as well as a voluntary imprisonment program.”[13] In other words, a person who is severely addicted is not likely to seek treatment without external factors pushing them in that direction.

Two international examples are helpful in understanding how to approach Canadian drug policy. Portugal overhauled its drug policy in 2001. Drug trafficking remains a criminal offence, but drug possession and use were decriminalized and became an administrative offence. People caught with drugs are brought before a dissuasion commission, which administers fines and points people towards treatment programs. A psychologist or social worker will interview a drug addict, and then a panel will offer suggestions about the best approach to stop drug use. The person is then fast-tracked to whatever services they are willing to accept. If help is refused, they may be required to do community service or pay a fine.[14]

Between 2008 and 2019, Portugal’s death rate due to drug overdose ranged from 10 to 72 across the entire country of over 10 million.[15] In 1999, comparatively, the country had 369 overdose deaths for a population of a similar size.[16] Recent reports, however, reveal that enforcement has become increasingly lax and drug use and overdose have increased in recent years.[17] Although Canada should not entirely emulate what has been done in Portugal (e.g., I have argued for criminalization of drugs rather than simply making drug use an administrative offence, as well as more involuntary treatment), we can learn from Portugal’s efforts to help drug users change through alternative penalties for an offence.

A second example is American states that have incorporated drug courts into their justice systems. Drug courts offer an alternative to incarceration and include a multidisciplinary team of professionals who can respond to individual cases. Based on a person’s risk and needs assessment, the court determines what kind of treatment should be provided and for how long. If a drug user successfully completes treatment without further drug use or criminal activity, any criminal charges for the initial drug conviction are dropped. If a person uses drugs while in treatment, the court determines whether to alter treatment or incarcerate the person. This approach does not eliminate a criminal record but provides the opportunity of doing so if the person is compliant with treatment. These courts have demonstrated a reduction in drug use and criminal activity and a decrease in incarceration rates. At the same time, it is estimated that drug courts save the state between $5,680 and $6,208 per person compared to incarceration.[18]

Because of the unique nature of drug use and abuse, with both health and criminal elements, the idea of ‘just desert’ requires a unique penalty. This is (and ought to be) applied in other areas of sentencing as well. A person who steals does not need to go to jail – they need to pay back what they have stolen. A person who commits a minor offence may not need to go to jail but instead be sentenced to probation so they can serve their sentence in the community. Prison, however, remains an option if the offender fails to meet the conditions of their sentence. Similarly, a person who is addicted to drugs may be sentenced to a treatment program that will help them get clean and reintegrate into their community. Depending on the particular offence and the number of times they have appeared before a court or commission, the penalty may vary from fines to treatment, with threat of incarceration as an incentive to complete treatment, and with incarceration only as a last resort.

Conclusion

The Canadian drug crisis is a challenging public policy problem. While incarcerating drug users has not worked to reduce drug use or reduce harm, decriminalization is also a flawed approach. The ideas of the image of God and moral agency help provide a better foundation for responding to the ongoing drug crisis. This series is an effort to consider drug policy through various Christian principles, while also looking at some of the practical elements and challenges of the drug crisis. I acknowledge that there are certainly no easy answers, and a wide range of possible approaches. Additionally, there are multiple pieces of the issue that I have not considered in depth in this series.

If you have any questions or comments on this series, please feel free to contact Daniel Zekveld at [email protected].

[1] Akm Moniruzzaman et al., “Public Supply of Addictive Drugs: A Rapid Review,” Simon Fraser University, Centre for Applied Research in Mental Health and Addiction.

[2] Adam Zivo, “Reckless: British Columbia’s “safe supply” fentanyl tablet experiment,” MacDonald Laurier Institute, December 2023.

[3] Derek Finkle, “’Safe injection’ ruined my community; about time for a provincial review,” National Post, Oct. 19, 2023.

[4] Tara Riley, as told to Derek Finkle, “Harm reduction gone rogue: I worked at a safe injection site and it was disturbing,” National Post, Nov. 30, 2023.

[5] Adam Zivo, “The Liberal government’s safer supply is fuelling a new opioid crisis,” National Post, May 9, 2023.

[6] Adam Zivo, “A 14-year-old is dead. Her dad blames ‘safer supply’ drugs,” National Post, May 31, 2023.

[7] See the Supreme Court of Canada’s landmark decision on conditional sentencing in R. v. Proulx, 2000 SCC 5, at para. 111.

[8] See R. v. Proulx, 2000 SCC 5, para. 111.

[9] Perrin, Overdose, 88.

[10] Tristin Hopper, “Some Canadian prisons now have clinics where inmates can freely use smuggled drugs,” National Post, Sept. 14, 2023.

[11] “The Drug Report: A Review of America’s Disparate Possession Penalties,” Prison Fellowship, 29.

[12] Rachel Emmanuel, “Meet the recovered drug addict who became the Alberta premier’s chief of staff,” True North, Jan. 2, 2023.

[13] Twenty-First Century Illicit Drugs and Their Discontents: Methamphetamine—The Downs of Ups, or Tweaking the Night Away | The Heritage Foundation

[14] Daphne Bramham, “Decriminalization is no silver bullet, says Portugal’s drug czar,” Vancouver Sun, Sept. 8, 2018.

[15] Beatriz Luz, “Number of drug overdose deaths in Portugal from 2008 to 2020,” Statista, Oct. 13, 2023.

[16] Niall McCarthy, “Then & Now Portugal’s Drug Decriminalization,” Statista, Jan. 24, 2020.

[17] Pat Dooris and Jamie Parfitt, “Portugal, the drug decriminalization success story Oregon followed, now appears to be in trouble,” KGW, July 21, 2023.

[18] “The Drug Report: A Review of America’s Disparate Possession Penalties,” Prison Fellowship, 26.

Drug users as moral agents

Increasingly, the drug crisis is presented as a health care crisis rather than a criminal one, particularly by proponents of decriminalization. After all, much of the crisis began with prescription opioids in a health care setting. The health care system helps treat drug addiction, particularly medical side effects, overdoses, and various treatment options. In many ways, the issue is related to health care because of the extensive health and social concerns involved in drug use and abuse. But does that mean we should do away with the criminal element entirely?

To present the drug crisis as solely a health care issue ignores the fact that individuals are moral agents, capable of making choices and responsible for those choices. They are not simply victims of their circumstances who cannot be held accountable for their actions. There are often circumstances that lead to wrongdoing such as addiction or other medical or mental health factors, but that does not negate responsibility for one’s actions. If drug use was solely a health care issue, it would make sense to remove any criminal law restrictions on drugs. However, since it is not just a health care issue, there remains reason for criminal penalties.

Choice in Drug Addiction

While initial use of drugs may be a choice, subsequent addiction is not a choice in the same way. Even initial drug use might not be a clear choice if a person is taking opioids for pain and becomes addicted to those painkillers.

Drug addiction is hard to overcome, no matter how badly a person wants to change. There are scientific explanations for this. A single dose of many addictive drugs produces a protein called iFosB, which builds up in the body’s neurons. Each time the drug is used, as more iFosB accumulates, it eventually flips a genetic switch causing changes to the brain that last long after drug use has stopped. This leads to irreversible damage to the body’s dopamine system and makes a person far more prone to addiction. As tolerance to the drug develops, a person needs more and more of it to get the desired effect. However, the brain also becomes sensitized to the drug, leading to increased cravings for the drug.

An addict does not just take drugs because of the sensation it provides or the discomfort of withdrawal. Instead, they will crave drugs before they go into withdrawal and even if there is no pleasure derived from use.[1]

At the same time, while recognizing the challenges of addiction, there is moral responsibility for the choice to use drugs or the lack of choice to escape addiction. Someone who is addicted to drugs or commits a drug-related crime needs help, but that does not negate their responsibility. The other side of a conversation about whether drug use is a choice is the choice to ‘get clean,’ to come out of addiction. Of course, changing behaviour will require help and support from the community, but drug addicts do have agency to make such choices. And many want to make such choices, but simply need encouragement and help to do so.

When we deny moral accountability, we eliminate personal responsibility. Many in our society prefer to see people as victims of their circumstances. For example, two young men in the U.S. were acquitted (though later convicted on retrial) for killing their parents because they had been sexually abused by their parents as children.[2] In this instance, the stated reason for the crime is horrible for anyone to experience and is not a choice, but the brothers had a choice about their response. In other cases, people choose to act a certain way but do not want to accept the consequences. Adults who smoke cigarettes have successfully sued tobacco companies when they develop cancer. A woman who entered a hot-dog eating contest and began to choke on a hot dog attempted to sue the sponsor of the contest.[3] These people refused to accept the consequences that came because of their own choices.

Crime or Disease?

In “The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment,” C.S. Lewis talks about how the “humanitarian” approach treats crime like a disease or as a result of a person’s circumstances. When crime is not viewed as moral wrongdoing, however, it is impossible to pardon it. This makes it impossible for the offender to make amends and seek change because he has a disease that he is powerless to fix. Now, as we’ve noted, there is something unique about drug use, which may or may not involve an explicit initial choice to use drugs and which addicts may desire to escape. It’s not a question of either punishing the wicked or tending the sick, a dichotomy which Lewis tears down. Instead, maybe both can be involved – punishment for the purpose of renewal.

Although Lewis’ essay addresses crime generally (and doesn’t mention drug use), it helps to see drug use through this lens as well. As Lewis writes, “How can you pardon a man for having a gumboil or a club foot? But the Humanitarian theory wants simply to abolish Justice and substitute Mercy for it.” If we simply treat drug use as a health care issue, equating it with club feet or cancer, that leaves no agency for the addict to escape his addiction and no possibility of pardon for the mistakes he has made. Shame is often associated with drug addiction. But if we treat it like a disease that someone has no control over, the addict has no agency to overcome that shame. We need to help people see that they can (and should!) overcome harmful behaviour that is ruining their lives. To give someone that hope of renewal and escape is to treat them as a person made in God’s image, punishing what is wrong, but also providing opportunity for change.[4]

The “humanitarian” approach to punishment eliminates the concept of ‘Desert;’ namely, that the punishment should fit the crime. And Lewis insists that there must be just desert for wrongdoing. But that raises the question of why – and how – drug use should be treated as a crime. Does it actually merit punishment?

Societal Responses

Advocates of decriminalizing drugs often point to the need to destigmatize drug use. Because agency remains when it comes to drug use, however, stigmatizing drug use is a worthy goal. As one journalist points out, “We, as a society claim we don’t like to stigmatize or judge and say shame is bad. But this is to act foolishly: shame and stigma are how we show errant members of society that they need to reform their ways and change for the better.”[5] Stigmatizing drug use will hopefully deter some Canadians from using drugs. We stigmatize the very things that we deem harmful.

Take, for example, smoking, which has been increasingly stigmatized in recent years, effectively reducing smoking habits in Canada. In fact, warning labels will be required on individual cigarettes later this year.[6] Warning labels on cigarette packs in the past have led to reduced smoking rates and have hindered youth from starting smoking. Such an approach is stigmatizing as well.

At the very least, there should be a cultural and societal stigma against drug use, encouraging addicts to get clean and disincentivizing others from getting started in the first place. It is important to continue to tell drugs users that what they are doing is harmful, not to mention illegal, rather than simply allowing them to continue in their addiction. The criminal law is one way of signaling what is deserving of prohibition and punishment.

Criminalization

Beyond stigmatizing drug use, should the government create criminal penalties for drug use? What is the government’s role in all this? From a biblical perspective, the role of the government is to administer justice. Because of the depravity of mankind, God has ordained kings, princes, and civil authorities.[7] He wants the world to be governed by laws and statutes, in order that the lawlessness of men might be restrained and that everything be conducted in good order. As we read in Romans 13:3-4, “For rulers are not a terror to good conduct, but to bad. Would you have no fear of the one who is in authority? Then do what is good, and you will receive his approval, for he is God’s servant for your good. But if you do wrong, be afraid, for he does not bear the sword in vain. For he is the servant of God, an avenger who carries out God’s wrath on the wrongdoer.”

Considering this, the government has a role in justice as it relates to drug use and addiction because of its relation to public safety. Drug use has public safety implications because it is so closely connected with other criminal activity. Drug use and addiction has a negative impact, not just on the individuals that use drugs, but on their families and communities as well. A recent American study also points to more industrial accidents, more injuries, and greater absenteeism among employees who use marijuana.[8] BC has seen skyrocketing rates of violence associated with drug use.[9] Since public justice is the role of the civil government, the government has a role in cleaning up crime. This means, at the very least, not stimulating drug use, but also preventing it.

But aside from the public safety elements, the use of illicit drugs should continue to be illegal. Part of this is what I noted above about the criminal law indicating what is acceptable and what is unacceptable conduct. The law, in many ways, is a teacher that influences actions. Charles Colson writes, “We should not be utopian about government’s ability to restrain sin; its ability is, of course, limited. Nonetheless, we are to work to make it as effective as possible.”[10]

As I thought about a policy response to drug use, various other issues arose as possible comparisons. Should criminalizing drugs be equated with criminalizing alcohol? Or should the government also ban other behaviours that it deems harmful? Or maybe drug use should only be illegal in public, but not in private? But the closest comparison I landed on is the issue of pornography. Much of the pornography available in Canada today has severe negative impacts on those viewing it, as well as on their families and communities. It is contrary to God’s law and violates human dignity. There is an element of addiction that changes the brain and makes it harder to quit. Initial exposure may or may not have been a choice. It can also lead to a variety of other criminal acts. Although it is not seen as a criminal problem in Canada, it ought to be. I would argue that each of these factors apply to the use of illicit drugs as well and justifies criminalization. (Where this comparison breaks down is the fact that there may be legitimate uses for some drugs in the proper context, such as painkillers, while the same is not true of pornography). Nevertheless, the scope of the problem and its effects on individuals as well as on communities suggests a need for legal prohibition.

Finally, there is a practical element to criminalization of drugs. Legal researcher Paul Larkin writes that “The cliché that ‘We can’t arrest our way out of this [predicament]’ is matched by the reality that ‘[w]e can’t treat our way out of it, either, as long as supply is so potent and cheap.”[11] Criminalization is part of the solution to the problem. But this also gets to the point that the penalty must also be appropriate, a ‘just desert’ where the punishment fits the crime. The final article of this series will consider possible ways forward and how Canadian governments can make the punishment fit the crime.

[1] Norman Doidge, “Acquiring Tastes and Loves: What Neuroplasticity Teaches Us About Sexual Attraction and Love” in The Social Costs of Pornography: A Collection of Papers, eds. James R.Stoner, Jr., and Donna M. Hughes (Princeton: Witherspoon Institute, 2010), 34.

[2] Colson, Justice That Restores, 62.

[3] Colson, Justice That Restores, 63.

[4] C.S. Lewis, “The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment,” Res Judicatae, 225.

[5] Adam Pankratz, “Maybe B.C.’s drug addicts should have to face shame and stigma,” National Post, Feb. 6, 2023.

[6] Adam Miller, “Cigarette warning labels are about to get even harder to ignore in Canada,” CBC News, May 31, 2023.

[7] Belgic Confession, Article 36.

[8] John Howard et al., “Cannabis and Work: Implications, Impairment, and the Need for Further Research,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, June 15, 2020.

[9] Aaron Gunn, “Canada is Dying,” YouTube, May 24, 2023. See also Kim Bolan, “Inside the battle by drug gangs for control of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside,” Vancouver Sun, Aug. 9, 2021.

[10] Colson, Justice That Restores, 47.

[11] Paul Larkin, “Twenty-First Century Illicit Drugs and Their Discontents: Methamphetamine – the Downs of Ups, or Tweaking the Night Away,” The Heritage Foundation, Dec. 21, 2023.

The Image of God

To know how best to tackle the distressing drug crisis in Canada, we first need to have a sense of what justice requires and what (or who) man is. To do so, we need to go right back to Genesis 1: “Then God said, ‘Let us make man in our image, after our likeness. And let them have dominion ….’ So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them.”[1]

The Image of God and Human Flourishing

The image of God has implications for how people take care of their bodies. At the same time, it points to the need to care for our drug-addicted neighbours. But we don’t stop at keeping drug addicts from dying. We ought to also consider the other harmful effects of drugs.

Even a comparatively mild and legal drug like cannabis can have negative influences on those who use it. Health Canada points to the short-term effects cannabis use has on the mind, including possible confusion, impaired cognitive ability, anxiety, or psychotic episodes such as paranoia or hallucinations. Long-term effects can include loss of memory, concentration, or IQ, with particular impact on youth and frequent users.[2] In 2022, 40% of hospitalizations of 10- to 24-year-olds for substance use were related to cannabis.[3]

Cannabis has all these potential side effects and is still legal in Canada. Effects of harder drugs include both physical and mental impacts on the body, such as risk of heart attack, violent behaviour, anxiety, paranoia, or hallucinations.[4] Drug use can also lead to decreased performance at work or school, changes in behaviour, and financial issues.[5] And of course, drug use can lead to addiction and potential overdose and death. Other criminal activity often arises alongside drug addiction as people seek a way to fund their addiction or resort to violence.

Drugs offered through government programs like ‘safe supply’ or ‘safe injection sites’ can include a variety of side effects as well. One commonly used drug known as hydromorphone or dilaudid has a similar range of possible side effects as other illegal drugs, although it is far less potent.[6] Some suggest hydromorphone may even be the cause of a segment of overdose deaths in Canada.[7]

The physical harms of drug use do not immediately necessitate government action. After all, the government cannot ban everything that is potentially harmful to people’s physical or mental health. That said, drug use is also not something that simply affects the user who makes an autonomous choice. Drug use does not happen in isolation, but deeply impacts families and communities.

The Image of God and Community

The importance of community is a key component of the image of God. The fact that we are made in the image of God means we were made to be in relationship. We bear the image of a relational God.[8] The three Persons of the Trinity are in perfect relationship with each other, and God has created us to be in relationship with others and with Himself. Drug addicts, too, were created to be in relationship. Whether or not these relationships have been broken because of their own choices, addicts also crave relationship and need those around them to help them overcome addiction. The need for relationship is also seen in the increasing loneliness and isolation in our society.

This element of relationality tells us that, while the government may have a role in responding to the drug crisis (a question I’ll address in the next article), it cannot have the only role. Instead, as Charles Colson writes, “Without individual virtue, we cannot achieve a virtuous culture… Without a virtuous culture, we cannot hire enough police to keep order.”[9] To be able to maintain a virtuous society, it is necessary to involve social institutions besides the state, such as families, churches, and community organizations.[10] Government is not best placed to build relationships and should partner with community organizations who can provide treatment and recovery services to drug addicts. One academic review confirms “In practical terms, the overwhelming majority of factors that contribute to harm reduction, or the prevention and treatment of addiction, involve relationships and are social.”[11] Being social, relational people is part of being created in the image of God. To recover from addiction, people need help from their families, communities and those around them, including Christian churches and organizations which can provide help to those in need.

When we talk about issues like drug use, we also note that there is hope for renewal, and each of these social institutions plays a role in that renewal. John Kilner writes, “The church will continue to call all people to renounce their sin and follow Christ, for renewal according to God’s image in Christ is the glorious fulfillment of what only began at creation. At the same time, the church can help show people the extent of God’s love by the way that Christians uphold the life and dignity of all – even the down and dejected, the needy and neglected, the ruined and rejected.”[12] A related role of politicians, then, is to make room for (and potentially incentivize) the work of Christian groups and organizations in responding to the drug crisis.

The Image of God and Public Policy

As our governments seek to respond to the drug crisis, we can encourage them to recognize and acknowledge the image of God in all Canadians. There is currently no objective foundation for how governments view people, including those addicted to drugs. A faulty anthropology leads to misunderstanding the real issue at hand. For example, if governing officials see human beings as essentially good, only corrupted by their surroundings, they may see no point in pushing drug users take responsibility for their lives and change their behaviour. At the same time, we can see in government responses in trying to save lives that they still understand some concept of the dignity of the human person, even if the source of that dignity is unclear to them.

We should note, however, that acknowledging the image of God does not simply mean keeping people alive as much as possible. Governments now tend to focus myopically on reducing overdose deaths. Of course, overdose deaths are tragic, and we should seek to reduce those numbers. But we ought not stop there. Drug use in itself is harmful to image-bearers and those around them, even if a person does not die from it.

The Image of God and Human Depravity

Scripture tells us to speak up for the poor and vulnerable and to care for those in need.[13] When we view our drug-addicted neighbours as created in the image of God, we have a foundation on which to address the drug crisis more effectively, without solely focusing on overdose deaths.

Of course, when we consider the image of God, we also need to go back to Genesis 3 recognizing that we are fallen and impacted by the effects of sin. We are morally responsible for our choices, but also inclined to sin.[14] Although we are unable to do any good without the work of the Holy Spirit, we maintain moral responsibility for the wrong that we do. I will look at moral agency in the next article of this series.

[1] Genesis 1:26-27.

[2] “Health effects of cannabis,” Government of Canada, Aug. 26, 2022.

[3] “Fewer young people being hospitalized for substance use, but overall rates still higher than before the pandemic,” Canadian Institute for Health Information, Nov. 30, 2023.

[4] Mayo Clinic Staff, “Drug addiction (substance use disorder),” Mayo Clinic, Oct. 4, 2022.

[5] Mayo Clinic Staff, “Drug addiction (substance use disorder),” Mayo Clinic, Oct. 4, 2022.

[6] “Hydromorphone, Oral Tablet,” Healthline, June 9, 2022.

[7] Adam Zivo, “A 14-year-old is dead. Her dad blames ‘safer supply’ drugs,” National Post, May 31, 2023.

[8] Hugh Welchel, “Relationships are Integral to the Mission of God’s People,” Institute for Faith, Work & Economics, April 27, 2015.

[9] Charles Colson, Justice That Restores (Wheaton, IL: Tyndale House Publishers, Inc, 2001), 105.

[10] Colson, Justice That Restores, 88.

[11] Akm Moniruzzaman et al., “Public Supply of Addictive Drugs: A Rapid Review,” Simon Fraser University, Centre for Applied Research in Mental Health and Addiction.

[12] John F. Kilner, Dignity and Destiny: Humanity in the Image of God (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2015), 330.

[13] See for example, Psalm 82:3-4, Proverbs 31:8-9, Proverbs 19:7, and Luke 6:31.

[14] See, for example, Heidelberg Catechism, Lord’s Day 3 and 4.

“If ever by some unlucky chance such a crevice of time should yawn in the solid substance of their distractions, there is always soma, delicious soma, half a gramme for a half-holiday, a gramme for a week-end, two grammes for a trip to the gorgeous East, three for a dark eternity on the moon.”[1]

In Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, the drug soma makes the populace happy and complacent. The government of this dystopia provides it to the people and teaches them to depend on it. If any pain or distress arises, citizens simply need to take soma to escape from the difficulties of reality.

But our society is not so approving of drug dependency. So how do so many become addicted? Why do some stay addicted while others succeed in quitting? What will help solve the problem of drug addiction? There are no easy answers. In this series, I start by reviewing the nature of the drug crisis in Canada and the factors that contribute to it. In the next two articles, we will look at how biblical principles can help inform our response to the problem. The final article of the series will suggest some possible solutions.

The nature of the drug crisis

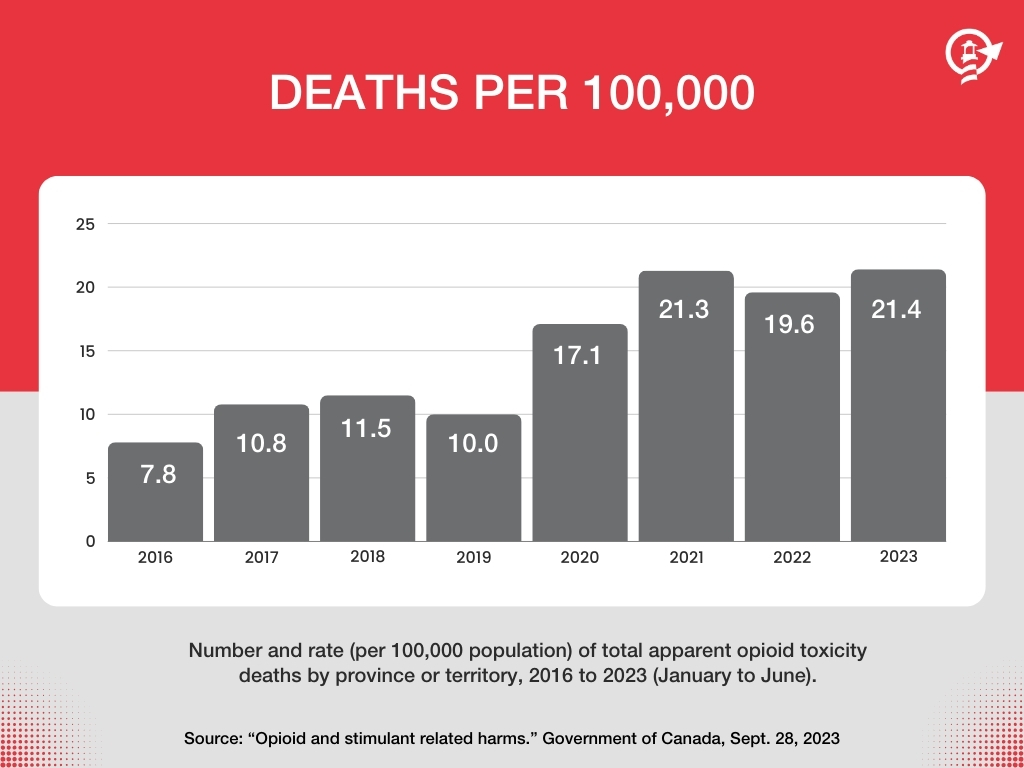

Between January 2016 and June 2023, over 40,000 Canadians died from drug use. Over the first six months of 2023, 89% of drug deaths happened in BC, Alberta, and Ontario (these three provinces make up only 64% of the Canadian population). 84% of opioid deaths involved fentanyl, and 80% involved non-pharmaceutical opioids.[2] In 2016, Canada averaged 7.8 deaths per 100,000 people from drug use, and that increased to 21.2 deaths per 100,000 by mid-2023.[3]

British Columbia has the highest rate of drug overdose deaths in the country. Drug deaths per 100,000 people per year in the province increased from 20.1 in 2019 to 48.3 in June 2023.[4] Alberta has the second highest rate, at 41.4 per 100,000 in June 2023.[5] Of the remaining provinces, overdose deaths per 100,000 are high in Saskatchewan and Ontario and relatively low in Quebec and Eastern Canada.[6]

Factors contributing to the drug crisis

Drug addiction in Canada exploded after OxyContin was introduced as a prescription painkiller in the 1990s. OxyContin was marketed as a non-addictive drug and readily prescribed to many patients. But it was highly addictive.[7] Overuse and misuse of prescription drugs increases the likelihood of illegal drug use and addiction, and this is what happened with OxyContin and other prescription drugs.[8] A significant amount of drug use stemmed from improper use of opioids (painkillers). While painkillers are necessary at times, they should not always be considered the first line of treatment and caution must be used to avoid addiction. The Christian Medical and Dental Association (CMDA) notes in a position statement that, “Christian healthcare professionals who know the unique hope Christ offers to suffering humanity should be alert to signs that a patient’s request for opioid medication for pain may signify or be part of a deeper need.”[9]

Another major factor in the increase of overdose deaths was the introduction of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is 30-50 times stronger than heroin. Just two milligrams of fentanyl is enough to kill a person.[10] It’s potency in small quantities makes it easier to smuggle and cheaper to distribute, but also more deadly.[11] In 2012, fentanyl was associated with just 4% of drug overdose deaths. This number rose to 87% in 2018.[12] Often, drug users will think they are buying heroin or another drug, when in reality they are buying fentanyl or a drug laced with fentanyl.

Cheap prices also worsen the drug crisis. Prices have fallen along with increased supply and relatively easy access to drugs.[13] For example, in Vancouver, morphine used to cost $20 per tablet. Now, the same amount costs $1.[14] In London, Ontario, prices for 8 milligrams of hydromorphone have decreased from $20 just a few years ago to $2 in 2023.[15]

The cost, availability, and potency of opioids are all factors in the ongoing drug crisis. But we also live in a society that is increasingly turning away from God. Francis Schaeffer explains that gradually in the 1900s the Christian foundations of Western society were removed, and life became largely meaningless. Schaeffer writes, “because the only hope of meaning had been placed in the area of nonreason, drugs were brought into the picture.”[16] Drug use became preferable to the meaninglessness of everyday life and the hope that was ultimately placed in material goods.

Many turn to drugs to escape the challenges of life, to dull pain, loneliness, or fear. Or a spirit of hedonism takes over, aiming to live for pleasure in the present with little regard for the future. Such people may start taking drugs occasionally but this occasional use, especially at younger ages when the brain is still developing, often grows into a dependence on drugs.

At the same time, our society is becoming more fragmented and isolated. According to a 2019 Angus Reid Survey, nearly half of Canadians were isolated, lonely, or both. Those least likely to be isolated or lonely are those who are married and have children and those who take part in faith-based activities.[17] As churches, families, and other institutions break down, social isolation grows. Social isolation is also linked to the development and exacerbation of opioid addiction.[18] The social isolation experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, intensified problems with drug addiction.[19]

Responses to the Problem

Throughout the country, possession of hard drugs is illegal. However, provinces can apply for exemptions under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. For example, British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Ontario, and Quebec have all received exemptions for various supervised consumption sites in their provinces. British Columbia has received an exemption from criminalizing possession of small amounts of drugs, and the City of Toronto has applied for a similar exemption. Officially, most drugs remain illegal under federal law.

Nevertheless, provinces respond to drug use and abuse in different ways. There are three overarching approaches that governments have used to combat the drug crisis.

Incarceration

Traditionally, the war on drugs meant that both drug dealers and users were subject to jail time, although drug use and possession were often only prosecuted when combined with other criminal offences. A wide range of substances are currently illegal under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, which clarifies offences and what the punishment should be. Recently, the federal government removed mandatory minimum penalties for several drug-related offences, giving more leeway to judges and more opportunity to apply alternative sentences.

Safe Supply and Harm Reduction

The major political parties have largely moved away from promoting jail time for minor drug offences. Increasingly, the dominant policy approach favours publicly funded access to drugs with the goal of harm reduction. Harm reduction, that is, trying to avoid overdose and death from drug use instead of punishing or discouraging drug use, is the buzzword in most drug policy circles today.

Last year, the province of BC decriminalized possession of up to 2.5 grams of hard drugs after the federal government granted them an exemption under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.[20] BC has also focused on providing so-called ‘safe supply.’ Safe supply “refers to providing prescribed medications as a safer alternative to the toxic illegal drug supply to people who are at high risk of overdose.”[21] The reason these drugs are called ‘safe’ or ‘safer’ is because the drug content is known and will be less likely to cause overdose. The drugs prescribed, however, are still powerful substances. Proponents of safe supply argue that it will not only reduce overdoses and deaths, but that it will also reduce crime because addicts will not have to steal to get enough money for drugs. Some believe it will allow drug users to manage their addiction and live normal lives.[22]

Canada’s first safe injection site opened in Vancouver in 2003.[23] The federal government began investing in safe supply programs, publicly funding the supply of addictive drugs, in 2020.[24] So the approach of British Columbia towards drugs is not entirely new. However, it is more focused and comprehensive than previous attempts.

The goal of the BC government in decriminalizing drugs is to “reduce the stigma and isolation that prevents people from reaching out for help and leads to people using alone.”[25] Yet the BC government also attempt to pass legislation to restrict the use of drugs in public spaces following concerns about drug use in communities, particularly near areas where kids play.[26] This law was stopped by a court injunction (in effect until the end of March) stating that this restriction would cause “irreparable harm” to drug users.[27]

Recovery-Focused Approach

The primary alternative drug policy approach in Canada is now commonly deemed ‘the Alberta model.’ It focuses on improving treatment and recovery options for drug addicts while continuing to prosecute both trafficking and possession of hard drugs. As the Alberta government states, “a recovery-oriented system of care is a coordinated network of personalized, community-based services for people at risk of or experiencing addiction and mental health challenges.” They note that such an approach requires a shift in philosophy, looking at drug abuse and recovery holistically.

Alberta still has safe consumption sites, where addicts can access drugs for the purpose of avoiding withdrawal symptoms as they work towards recovery. However, the province tracks data and information about usage and uses the safe consumption sites as a means to encourage addicts to enter treatment and recovery. Addicts must take the drugs at the clinic where they receive them, and the clinic will work with the addict to try to help them recover. Alberta is also increasing access to treatment beds and has eliminated the fee previously required for treatment beds. They have also created a Narcotic Transition Program which allows drug addicts to start treatment on powerful opioids to avoid withdrawal, and slowly reduce the amount they consume.[28]

Elements of treatment and recovery are not new to provincial responses to drug abuse, but Alberta’s approach is more focused than previous attempts. The Alberta model is “based on the belief that recovery is possible, and everyone should be supported and face as few barriers as possible in their pursuit of recovery.”[29] The Alberta model has been a significant focus of that government since 2023, although elements of it began in 2019.[30]

A complex policy issue

There are many aspects to drug policy including the psychology and treatment of addiction, the costs and benefits of criminalizing hard drugs, the societal impacts of drug addiction, the need to protect the lives of addicts while also dissuading the public from drug use, the extent to which the government should be involved in the first place, and so on. Similarly, there are many potential ways of addressing problems of drug trafficking, drug experimentation and addiction, and rising overdose deaths.

Canada’s drug crisis is one which might be called, in public policy, a ‘wicked problem.’ Wicked problems are hard to define and even harder to solve. A large part of the challenge is also the conflicting values and interests between adherents of the various perspectives on the issue. For example, when discussing drug policy, liberals might believe that drug use is a health problem, and that the solution is for the government to simply aim to reduce bodily harm. Libertarians might view this issue through the lens of freedom and autonomy and think that the government has no authority over what substances people put into their bodies or how they recover. People on the conservative side of the political spectrum may consider drug use to be a moral issue with the proper response being the criminalization of drug use and trafficking. All three of these underlying perspectives – health, freedom, and morality – are important, but how can we balance these three perspectives?

Stay tuned for more articles in this series, in which I hope to break this wicked problem down further and discuss how biblical principles help inform an effective public policy response to Canada’s drug crisis, how the image of God informs public policy, how moral agency factors in, and what role the government should play in responding to drug use and abuse.

[1] Aldous Huxley, Brave New World (New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, 1946) 62.

[2] “Opioid- and Stimulant-related Harms in Canada,” Government of Canada, December 2023.

[3] “Opioid- and Stimulant-related Harms,” Government of Canada, Sept. 28, 2023.

[4] “Opioid- and Stimulant-related Harms,” Government of Canada, Sept. 28, 2023.

[5] “Opioid- and Stimulant-related Harms,” Government of Canada, Sept. 28, 2023. See also “Alberta substance use surveillance system,” Government of Alberta, Dec. 2023.

[6] “Opioid- and Stimulant-related Harms,” Government of Canada, Sept. 28, 2023.

[7] “The US drug abuse epidemic is killing 300 Americans a day,” Al Jazeera, The Bottom Line, June 8, 2023.

[8] “Misuse of Prescription Drugs Research Report: Overview,” National Institute on Drug Abuse, June 2020. See also “Prescription Opioids and Heroin Research Report: Introduction,” National Institute on Drug Abuse, Jan. 2018.

[9] “Opioids and Treatment of Pain,” Christian Medical and Dental Association, April 21, 2020.

[10] Benjamin Perrin, Overdose (Toronto, Canada: Penguin Random House, 2020), 17.

[11] Perrin, Overdose, 60.

[12] Perrin, Overdose, 13.

[13] Line Editor, “Q & A, Part 2: ‘Our fatal overdose numbers have gone down dramatically off the peak’”, The Line, Jan. 13, 2023.

[14] Line Editor, “Q & A, Part 2: ‘Our fatal overdose numbers have gone down dramatically off the peak’”, The Line, Jan. 13, 2023.

[15] Adam Zivo, “The Liberal government’s safer supply is fuelling a new opioid crisis,” National Post, May 9, 2023.

[16] Francis Schaeffer, How Should We Then Live?: The Rise and Decline of Western Thought and Culture (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2021): 235.

[17] “A Portrait of Social Isolation and Loneliness in Canada today,” Angus Reid Institute, June 17, 2019.

[18] Nina C. Christie, “The role of social isolation in opioid addiction,” Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 16(7) (July 2021): 645-656.

[19] Alexiss Jeffers et al., “Impact of Social Isolation during the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health, Substance Use, and Homelessness: Qualitative Interviews with Behavioral Health Providers,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(19) (Oct. 2022). See also Aganeta Enns et al., “Evidence-informed policy brief – Substance use and related harms in the context of COVID-19: a conceptual model,” Public Health Agency of Canada, Sept. 16, 2020.

[20] Michelle Ghoussoub, “B.C. will decriminalize up to 2.5 grams of hard drugs. Drug users say that threshold won’t decriminalize them,” CBC News, June 3, 2022.

[21] “Safer supply,” Government of Canada, April 25, 2023.

[22] Perrin, Overdose, 170.

[23] Vancouver’s supervised injection site, the first in North America, opened 13 years ago. What’s changed? | National Post

[24] Future of Canada’s first-ever ‘safer supply’ drug program uncertain with funding set to end in spring | CBC News

[25] “B.C. takes critical step to address public use of illegal drugs,” BC Gov News, Oct. 5, 2023.

[26] “B.C. takes critical step to address public use of illegal drugs,” BC Gov News, Oct. 5, 2023.

[27] Tristin Hopper, “Why B.C. ruled that doing drugs in playgrounds is Constitutionally protected,” National Post, Jan. 2, 2024.

[28] Adam Zivo, “The UCP’s victory in Alberta is a win for Canadian addiction policy,” National Post, June 3, 2023.

[29] “The Alberta Model: A Recovery-Oriented System of Care,” Government of Alberta, 2023.

[30] “The Alberta Model: A Recovery-Oriented System of Care,” Government of Alberta, 2023.

After each federal election, the Prime Minister’s office releases Mandate Letters for each of the cabinet ministers. These letters explain the Prime Minister’s expectations for each member of his cabinet and lay out challenges and commitments that come with their role. At the same time, these letters are made publicly available so that Canadians can understand some of the priorities that the federal government will focus on over the next few years.

The ministers’ mandate letters were released on December 16, 2021. The basic template of each letter focuses on recovery from COVID-19, climate change, the rights of Indigenous Peoples, systemic inequity of minority groups within Canada, and general expectations for ministers. Many of the objectives and commitments in the letters are similar to what the government had promised prior to the election, so there are no major surprises. However, specific commitments are worth noting as we keep an eye on how they develop over the coming years.

Charitable Status

In line with the Liberals’ election promise regarding charitable status for certain organizations, the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance has been tasked with the following: “Introduce amendments to the Income Tax Act to make anti-abortion organizations that provide dishonest counselling to pregnant women about their rights and options ineligible for charitable status.” It’s unclear how exactly the government would remove charitable status from pro-life organizations or how far that would extend. However, the possibility is very concerning, and ultimately the government needs to recognize the value and importance of organizations like pregnancy care centres.

Hate Speech

Before the summer break in 2021, the government had introduced both Bill C-10 and Bill C-36, which focused on hate speech and regulating online content. Although those bills died when the election was called, the Liberals are once again focused on regulating and limiting freedom of expression both online and in public. The Minister of Housing and Diversity and Inclusion was given the following task: “As part of a renewed Anti-Racism Strategy, lead work across government to develop a National Action Plan on Combatting Hate, including actions on combatting hate crimes in Canada, training and tools for public safety agencies, and investments to support digital literacy, to prevent radicalization to violence and to protect vulnerable communities.”

In addition, the Minister of Justice will “continue efforts with the Minister of Canadian Heritage to develop and introduce legislation as soon as possible to combat serious forms of harmful online content to protect Canadians and hold social media platforms and other online services accountable for the content they host, including by strengthening the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Criminal Code to more effectively combat online hate and reintroduce measures to strengthen hate speech provisions, including the re-enactment of the former Section 13 provision.” This seems to be a replication of what was previously Bill C-36. However, there is a possibility that this legislation will include positive components around combatting online pornography as well as more negative limits on freedom of expression. ARPA Canada’s analysis of last year’s Bill C-36 can be found here.

The Minister of Canadian Heritage is expected to “reintroduce legislation to reform the Broadcasting Act to ensure foreign web giants contribute to the creation and promotion of Canadian stories and music.” The previous version of this legislation, Bill C-10, also included the possibility of regulating social certain private social media content that was determined to be a ‘broadcast.’ Further information around Bill C-10 can be found here.

We will be keeping watch to see what exactly is included in this type of legislation if and when it is introduced.

Pre-born Children

The government often speaks of ‘sexual and reproductive health’ to refer to abortion access. The recent mandates encompass that, and also specifically include issues such as in vitro fertilization and surrogacy. The Minister of Health is mandated to: “work to ensure that all Canadians have access to the sexual and reproductive health services they need, no matter where they live, by reinforcing compliance under the Canada Health Act, developing a sexual and reproductive health rights information portal, supporting the establishment of mechanisms to help families cover the costs of in vitro fertilization, and supporting youth-led grassroots organizations that respond to the unique sexual and reproductive health needs of young people.”

The Minister of Finance and the Minister for Women and Gender Equality and Youth are tasked with “expand[ing] the Medical Expense Tax Credit to include costs reimbursed to surrogate mothers for IVF expenses.”

One issue here is the clear plan to continue pressuring the province of New Brunswick to fund abortions in private clinics, something they are the only province not to do. More on that topic can be found here.

The focus on in vitro fertilization and surrogacy raises questions and concerns about how far these procedures might become commercialized in Canada. For further information on these issues, you can read ARPA Canada’s policy reports on both in vitro fertilization and surrogacy.

Gender and Sexuality

Regarding issues of gender and sexuality, the mandate letters only speak in broad terms, especially since Bill C-4, which banned so-called ‘conversion therapy’ was passed before the mandate letters were released. There is a lot of language around efforts to promote equality and remove discrimination for minority groups both in Canada and around the world.

The Minister of Justice is told to: “Build on the passage of Bill C-4, which criminalized conversion therapy, [and] continue to ensure that Canadian justice policy protects the dignity and equality of LGBTQ2 Canadians.”

The Minister for Women and Gender Equality and Youth is directed to “launch the Federal LGBTQ2 Action Plan and provide capacity funding to Canadian LGBTQ2 service organizations” and “continue the work of the LGBTQ2 Secretariat in promoting LGBTQ2 equality at home and abroad, protecting LGBTQ2 rights and addressing discrimination against LGBTQ2 communities, building on the passage of Bill C-4, which criminalized conversion therapy.”

It is hard to say what ‘building on the passage of Bill C-4’ looks like exactly because specifics are not provided. However, Bill C-4 is concerning on multiple levels, and building on it will likely follow in a similar vein. Further information on Bill C-4 can be found here.

Child Care

Child care continues to be an issue the federal government is pushing. The Minister of Families, Children and Social Development is tasked with concluding negotiations with provinces that have not yet signed an agreement with the federal government (Ontario and New Brunswick), and ensuring that $10-a-day child care is available throughout Canada. They also plan to “introduc[e] federal child care legislation to strengthen and protect a high-quality Canada-wide child care system.” You can read more about a Christian perspective on universal child care here.

Drug Use

The Minister of Mental Health and Addictions is tasked with advancing “a comprehensive strategy to address problematic substance use in Canada, supporting efforts to improve public education to reduce stigma, and supporting provinces and territories and working with Indigenous communities to provide access to a full range of evidence-based treatment and harm reduction, as well as to create standards for substance use treatment programs.”

This is not a new issue but there seems to be a new emphasis on it. Bill C-5, a reiteration of Bill C-22 from the previous Parliament, seeks to move increasingly towards treating substance abuse as a health issue instead of a criminal issue.

Conclusion

The issues presented here are priorities of the federal government, and they also raise various questions and concerns about what changes to legislation and regulations on these topics will look like. Stay tuned for further resources and action items as we see how these issues develop over the next few years.

I will always remember my first experience visiting a prison. I was in my University choir, and we stopped at a medium-security prison while on tour to sing for their chapel service. Throughout our performance and through our brief interaction with inmates afterwards, many of them were brought to tears and were amazed that a group of University students would sing for them and chat with them. The whole choir received a letter from one of the people imprisoned there following the visit, and he explained how that performance reminded them of their dignity and humanity.

Charles Colson, founder of Prison Fellowship Ministries, provides a helpful definition of what justice should look like: “A system of true justice … holds individuals responsible for their actions … under an objective rule of law, but always in the context of community and always with the chance of transformation of the individual and healing of fractured relationships and of the moral order (p. 101).” The question remains, does Canada’s justice system reflect this definition?

Changes to Criminal Sentencing

Bill C-22 is currently being debated in the House of Commons and addresses some important principles of justice as defined above. This is a government Bill that seeks to amend the Criminal Code and the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act in an effort to improve our justice system. The Bill would include amendments to remove mandatory minimum prison sentences for 20 different offences. Under the Criminal Code amendments, this would include firearms offences such as possessing, manufacturing, importing, or exporting a restricted weapon, or other crimes committed with the use of a firearm (excluding violent crimes such as attempted murder, kidnapping, and sexual assault). Amendments to the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act would remove mandatory minimum penalties for drug trafficking, drug imports or exports, or drug production. It would also reduce certain maximum sentences and provide greater opportunity for conditional sentencing.

The stated goals of the bill include addressing the root problems of crime through education, rehabilitation, and other means while seeking to protect health and human rights and reduce harm in society. Additionally, the legislation states that problematic substance use is a health and social issue and should be treated as such, with concerns that greater criminal sanctions can increase the stigma associated with drug use. Finally, the government says that Bill C-22 will address systemic racism by reducing the percentage of minority populations that are imprisoned through mandatory minimum penalties.

What the Bill Does Well

Bill C-22 would give a judge greater discretion to promote alternatives to imprisonment when sentencing an offender for specific offenses, dependent on individual circumstances. Because mandatory minimum penalties would be removed for certain crimes, offenders may be sentenced to house arrest, probation, curfew, mandatory counselling, or treatment for substance abuse. For example, if a person is charged with possession of illegal drugs for the purpose of drug trafficking, they may be sentenced to house arrest rather than a mandatory minimum of one year in prison. Of course, prison is not completely off the table: a judge could still hand down a prison sentence to the offender if he considered it to be reasonable.

As our culture dismisses Christian morals and glorifies sinful excess, the family unit suffers as criminal activity tends to increase. For example, crime and substance abuse have been shown to be strongly linked to fatherless households. Alternative sentences to imprisonment may help keep families together, while continuing to recognize the importance of offenders taking personal responsibility for their actions. Alternative sentences for minor crimes can be effective in reducing crime rates by helping offenders change their behaviour outside of the prison system. They can also prevent criminals from being affected by bad influences in prison.

In addition, this bill may create more room for private, non-profit, and other civil society organizations who seek to transform and rehabilitate offenders. Christian organizations may be able to provide counselling or mentorship to a larger number of offenders, and to help them reintegrate into society. As a result, it can help reduce the strain on the Canadian justice system, giving law enforcement the opportunity to put greater focus on other criminal and public safety concerns.

What the Bill is Lacking

While Bill C-22 allows for greater flexibility in terms of minimum sentences, it also reduces some of the maximum sentences, allowing for less flexibility in terms of longer sentences for the truly dangerous offender. Concerns have also been raised about mandatory minimum penalties being removed for some of the criminal offences, especially certain firearms offences. Discharging a firearm with intent, or out of recklessness is more concerning than drug possession, and both would have mandatory minimum penalties removed. Likewise, although sentences for theft over $5000 might be served well in the community through house arrest or restitution, kidnapping or sexual assault sentences (crimes which this bill would allow conditional sentences for if less than a two-year sentence) may be better served in prison. There should be a discussion on which crimes should and should not have mandatory minimum penalties, but the principle is a step in the right direction for non-violent crimes which can be effectively addressed outside of the prison system.

Additionally, while health and social concerns are involved in drug use and abuse, the federal government should still recognize drug use as a criminal issue, rather than an issue that simply needs to be “destigmatized.” Many in Canada today see humans as basically good by nature and believe that if a person breaks the law, it is because of social or economic circumstances, rather than a sinful decision or action. As Christians, we know that humans are sinful actors and that every crime is a moral choice. And while we should have compassion and understanding for those dealing with addiction, this moral choice cannot be ignored. Our justice system must continue to understand that criminal behaviour is a harmful choice by moral actors. Someone who commits a drug-related crime needs help, but the justice system should also endeavor to ensure that the crime is not repeated and that the crime is punished appropriately.

The recommendations in ARPA Canada’s policy report on Restorative Justice include using conditional sentences (i.e. house arrest) more frequently, and reserving mandatory minimum sentencing for violent crimes and offenders who are a danger to the community, and prioritizing diversity in sentencing as an alternative to imprisonment. While the details of Bill C-22 may need to be worked out further, there are some important principles addressed within it. The removal of certain mandatory minimum sentences allows for more opportunity to positively affect criminal behaviour through alternative sentences and treatment where necessary.

Prison sentences have not been shown to effectively improve criminal behaviour. Depending on the crime committed, it may be better for offenders to serve time in the community. House arrest still separates an offender from the community, while seeking to maintain principles of being a good member of that community. This can be done through counselling, or by being able to keep working and provide for their family. Drug offenders may have the opportunity to change through a rehab program. Old Testament principles of restitution show that theft can be punished by requiring the offender to restore or pay back what he stole. As much as possible, our justice system should seek to restore relationships broken by crime. Especially for minor crimes, letting offenders sit in jail may not be the answer. Our communities can seek to transform the lives of criminal offenders while continuing to recognize the importance of punishment for crime.

Real Transformation

As Christians, we seek transformation on a personal, community, and national level, knowing that Christ is the One Who changes lives, and He is the King of our nation. As with other political and societal issues, Christians can provide a unique perspective on criminal justice, and Christian organizations can seek to promote a true sense of human dignity, personal responsibility, and transformation in Christ.

by John Sikkema

by John Sikkema

Parliament is well on its way to legalizing marijuana. Bill C-45, the “Cannabis Act”, has passed in the House of Commons and is now in the Senate. It will likely be law early next year.

Our government acknowledges marijuana is harmful, particularly for young people. So it proposes to severely punish selling to a young person, while legalizing a recreational marijuana market. But if pot becomes more pervasive and easily available than it is today – as current investment in massive marijuana grow-ops suggests it will – it isn’t likely to stay out of young people’s hands.

It’s easy to be apathetic about this. Walk around a Canadian city for a while and there’s a good chance you’ll smell pot smoke, even though it’s illegal to possess it without a medical license. People are doing it anyway, the thinking goes, so why not regulate and tax it instead of prohibiting it?

We’ve been inundated with this kind of rhetoric: Our laws have failed. Prohibition doesn’t work. People are doing it anyway. Criminalizing it just makes the profits go to criminals. And so on. For years, leading publications like The Economist and The New York Times have been calling for legalization.

This narrative leaves out some important facts. First, prohibition hasn’t really been tried and found wanting in recent years. It’s been found cumbersome and left largely untried. Halifax’s Police Chief said, “Small seizures [of marijuana] are higher maintenance than public drinking. The person with the bottle of booze is given a ticket; the person with the joint requires three to four hours of police work,” he said. “If the case goes to court, and it’s a first-time offence, the case may be withdrawn.” The Montreal Gazette reported that it could not find anyone in the city who had been in prison for basic possession (under 30 grams).

As the Vancouver Police Department reportedly stated, “the VPD does not place a high investigative or enforcement priority on people for cannabis possession only. In fact, where charges are recommended, in the vast majority of cases the cannabis possession charge is one of usually several more serious offences involved in the same incident.” So, police avoid enforcing the law. Obvious incidents of possession are typically overlooked – which is why it’s so common to see and smell people smoking pot. And while there are still thousands of possession-related arrests in Canada each year, charges are not laid in most of them.

Marijuana use is growing as the law is flaunted. There are even a few stores that sell pot directly to customers who walk in without medical use licenses.

Now we’re on the cusp of national legalization. Finally, “freedom” is coming to Canada, but the latest CBC headlines heralding its near arrival are somewhat surprising:

- “Pot black market isn’t expected to disappear even as marijuana becomes legal” (Dec 4)

- “Province [B.C.] way behind in dealing with marijuana-impaired driving, says lawyer” (Dec 5)

- “Legal pot could see justice costs climb, not drop, [Premier] Rachel Notley says” (Nov 23)

- “Marijuana legalization coming too fast to ensure public safety, says head of Alberta police chiefs” (Nov 16)

- “Black market will thrive if Alberta government runs marijuana stores, says mid-level dealer” (Oct 8)

It’s a bit of a contrast with some stories CBC was running in 2015. Like a puff piece on a guy convicted for illegally selling marijuana – he claimed it was for people with medical needs – who is now calling on the government to pardon him and others convicted of marijuana-related offences and to offer a public apology for prohibition. Or a story about how “Saskatchewan is the place you’re most likely to get busted for simple possession,” with a picture of a middle-aged man in a batman shirt holding a big bag of weed (the photo makes the case against legalization). His Saskatoon store is called “Skunk Funk”. He’s not in jail.

In my view, the government is taking the wrong direction. It should be trying to find simpler ways to suppress marijuana use. Legalization and government distribution will achieve the opposite.

The former Conservative government may have missed an opportunity here. Instead of enacting mandatory minimum sentences for offences like marijuana possession (an offence which is hardly enforced), they could have moved to a system of fines, strictly enforced. Locking someone up for possessing marijuana (which is almost never done because police, prosecutors, and judges are opposed) is very expensive and, like pot smoking, liable to make them a worse citizen and less likely to get a job. Of course, a person is responsible for his choices. But there are better ways to punish non-violent offences than prison. Prisons are good for mainly one thing – separating dangerous persons from society.

Current laws are ineffective mainly because police, prosecutors, and judges don’t enforce the law. Obviously, much of that was outside the previous government’s control. But police did call for an alternative, as the CBC reports: “Two years ago, the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police called for the option to write a ticket for simple possession, noting […] their only choice is to lay charges or turn a blind eye.” It just didn’t seem worth it to most police officers to lay charges and do the paperwork. It didn’t seem worth it to prosecutors to commence criminal proceedings. It didn’t seem worth it to judges to punish possessors. A fine was an option for first time offences, but this didn’t serve as much of a deterrent because it too was hardly used. It would require a criminal trial and result in a criminal record.

With marijuana use so common and complacency so ingrained in the criminal justice system, perhaps a simpler deterrent is needed. Perhaps federal legalization will create an opportunity for a wiser provincial government to suppress marijuana use by making it a provincial offense, like a traffic ticket. Simplify enforcement and generate revenue from fines. Don’t get provincial government involved in the sale and distribution of cannabis – which would give young people more than a whiff of societal approval.

By John Sikkema

“Safe” or “supervised” injection sites provide drug users with clean needles and medical supervision for injecting narcotics. So far, there are none in Canada outside of Vancouver.

“Safe” or “supervised” injection sites provide drug users with clean needles and medical supervision for injecting narcotics. So far, there are none in Canada outside of Vancouver.

But that is likely to change. Parliament just made it a lot easier to establish safe injection sites with Bill C-37, which passed earlier this month. Canada’s Health Minister is currently reviewing 19 applications for such sites, and more applications are expected.

Another win for “harm reduction”

You may recall the 2011 Insite case (Canada v PHS Community Services Society), in which the Supreme Court of Canada decided that the federal government must allow Insite, a publicly funded safe injection site in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (DTES), to operate. The evidence was conclusive, in the Court’s view: “Insite has been proven to save lives with no discernible negative impact on the public safety and health objectives of Canada.” This was a major legal victory for “harm reduction”.

Insite presented evidence to the courts that people were saved from overdose and infection within its walls. The government failed to counter with evidence to show that permitting safe injection sites discernibly undermines its policy objectives – which is a lot more complicated.

Many celebrated the Supreme Court’s ruling as a triumph of evidence-based harm-reduction techniques over failed hardline conservative anti-drug policy. Others (including me) were critical of the Court’s casual readiness to reverse the social policy of Canada’s democratically elected government and to discover a right to possess and inject narcotics with help from medical personnel, immune from prosecution.

A Globe and Mail headline announced the ruling: “Supreme Court ruling opens doors to drug injection clinics across Canada”. The Supreme Court offered the following as a guiding principle for when safe injection clinics should be permitted to operate: “Where, as here, the evidence indicates that a supervised injection site will decrease the risk of death and disease […] the Minister should generally grant an exemption [to the prohibitions on narcotics possession].”

However, six years after the Insite ruling, only one new safe injection site has opened in Canada, along with a few mobile sites – all in Vancouver. The lack of new facilities is due in part to the Conservative government’s legislative response to the Insite ruling; it enacted a list of requirements that would-be supervised injection sites had to satisfy before becoming operative. Bill C-37 removes most of those – another big win for harm reduction advocates.

Walking the DTES

A Globe and Mail story (Jan 1, 2017) describes an awful scene in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (the DTES). The reporter watches a woman and her friend prep a needle full of crystal meth, within view of an employee of a needle exchange program who is trying to revive an overdosing man. Firefighters and paramedics arrive; they believe it’s the same man they helped in the same place the day before.

The woman and her friend inject themselves with meth, “the scene in front of them no deterrent”, the reporter notes.

It’s “Welfare Wednesday”, the day of the month when welfare cheques go out and “millions of dollars of social-assistance payments flood into the Downtown Eastside.” On this day, overdoses increase “dramatically” and “there is a constant wail and yelp of sirens.”

Street dealers sell drugs to “dozens of people injecting in the alley”, not far from a “pop-up supervised drug consumption tent”. Meanwhile, Insite is “completely swamped”.