Do women who choose to have an abortion live just as happy and healthy lives as those who choose to keep their child? The pro-choice side argues yes. In fact, having an abortion will make them better off, they would say. But we’ve written many times about how abortion is not only bad for the child but also bad for women.

A recent study out of Quebec investigated this question anew. It concludes that “abortion is associated with an increased risk of mental health-related hospitalization in the long term” (emphasis added).

The study analyzes 1.2 million pregnancies in Quebec from 2006 to 2022. The authors followed 28,721 women who had an abortion and 1,228,807 women who gave birth to see if these women had any differences in mental health-related hospitalization. And they looked at the long-term effects of abortion on mental health, tracking outcomes for up to 17 years.

Both the size and location of the study are significant. Many of the other studies examining outcomes for women after an abortion are relatively small or focus on just a sliver of the population. For example, one study looked at just 325 patients in the Netherlands. Another study considered more than 12,000 women in Finland, but only teen pregnancies. A Danish study examined over 74,000 cases, but only women with no history of mental disorders.

A strength of this Canadian study is that it examines a massive number of women (1.2 million) and pretty much the entire population (of Quebec). The larger the sample, the more confident researchers can be with their results. Furthermore, the more representative a study sample is (e.g. how closely it matches the real world), the more reliable the results. This study checks both boxes.

This is also a Canadian study. While there are commonalities between women seeking abortions around the world, there are also important differences in different countries. Canada is the only country in the world with no legal restrictions on abortion, making attitudes towards abortion different from, say, the United States. On the other hand, Canada provides less social assistance than, for example, the Nordic countries, so more women might feel financial pressure to have an abortion. The closer to home a study is, the more applicable it is to your own country (all other things being equal).

So what are the results of the study?

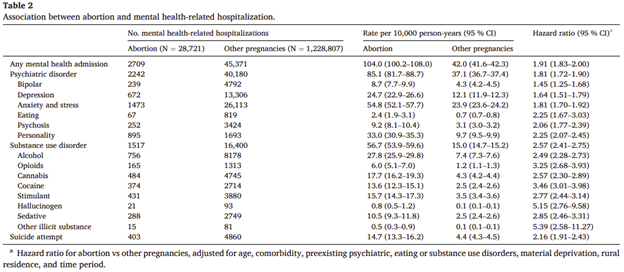

The study concludes that women who have an abortion are far more likely to be hospitalized for a mental health condition than women who choose to keep their child. Overall, women who had an abortion had a mental health-related hospitalization rate two and a half times higher than women who kept their child (104 vs 42 mental health-related hospitalizations per 10,000 person-years).

And this pattern of post-abortive women having a higher likelihood of mental health-related hospitalization holds for any mental condition. They have higher rates of hospitalization for bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety, eating disorders, psychosis, and personality disorders. They also have higher rates of misuse of alcohol, opioids, cannabis, cocaine, stimulants, hallucinogens, sedatives, and other illicit substances. Hospitalizations from suicide attempts were higher, too.

Because of the sheer number of women included in the study and the magnitude of these differences between the two groups, these differences are statistically significant. In other words, they aren’t due to chance. And they are very unlikely to be due to other factors, as the authors already controlled for other factors (e.g. age differences or preexisting psychiatric conditions) that might be the real cause of the differences. Having an abortion was correlated with these mental health-related hospitalizations.

Furthermore, the women in this study who opted for an abortion were not all that different than those who chose to keep their child. The data simply doesn’t paint one group as desperately needing an abortion and the other as comfortably able to care for a child. Looking at the descriptive statistics, the women who chose an abortion were more likely to be under 20 years old compared to the women who gave birth (11.1% vs 2.1%) and have a preexisting mental condition (11.3% vs 6.3%). But they were also less likely to have a comorbidity (2.8% vs 5.2%). The rate of material deprivation (23.6% vs 20.0%) was similar for both.

As the study simply tapped into an existing dataset, the researchers couldn’t ask all these post-abortive women why their mental health worsened or why they turned to substance use at higher rates. But the most likely answer is that, deep down, these women know they made the wrong choice. After all, as feminist Frederica Matthewes-Green said, “There is a tremendous sadness and loneliness in the cry ‘A woman’s right to choose.’ No one wants an abortion as she wants an ice-cream cone or a Porsche. She wants an abortion as an animal, caught in a trap, wants to gnaw off its own leg.” This is something that wood floors and comfy chairs can’t fix.

Time can help, though. The study found that mental health-related hospitalization for post-abortive women was most frequent in the first five years after having an abortion, but that this increased risk declined over time. By the end of the study’s follow-up (up to 17 years later), having had an abortion was no longer associated with a mental health hospitalization.

At the end of the day, this new Canadian study bolsters the pro-life movement’s claim that it is not fundamentally anti-women or anti-choice. In reality, we are pro-women and pro-the-right-choice. And we want women to have the best mental health outcomes possible. That means choosing life over abortion.

On February 28, Liberal MLA Iain Rankin introduced Bill 56: Harvey’s Law in Nova Scotia. If the name sounds familiar, that’s because another MLA (Keith Irving) introduced an identical bill back in 2021 and again in 2024. A similar bill, Harvey and Gurvir’s Law, was also introduced in Ontario in 2021.

Bill 56 would require the Minister of Health and Wellness to ensure that up-to-date, evidence-based information on Down syndrome is available to members of the public. This information must include elements such as life expectancy, cognitive and physical development, and education and psychosocial outcomes for people with Down syndrome. It would also include information about resources and supports available to those who have a family member with Down syndrome. Further, when a health professional communicates a prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome to expectant parents, they must give them the up-to-date information relating to Down syndrome.

Irving introduced this bill because of a local family’s difficulty getting balanced information after learning that their son, Harvey, had Down syndrome. Following the prenatal diagnosis, Harvey’s mother Sarah was referred for multiple tests. Throughout this process, she was told by various health professionals about things Harvey would be unable to do and questioned about why she would not get an abortion.

It was only through their own research that Harvey’s parents learned that their son would be able to thrive. Many of the things they were told Harvey would be unable to do were factually incorrect. Because of the challenges in accessing accurate information, and the desire to save other families from the same problem, Harvey’s mother began advocating for Harvey’s Law, first in Ontario and more recently in Nova Scotia.

In a culture that so readily aborts pre-born children with Down syndrome, Canadians need to change their mindset about children with a fetal abnormality. People need to know that children with Down syndrome are valued, live meaningful lives, and that there are supports for challenges that may arise.

Bill 56 would help to change the tone of conversations that parents have with their healthcare providers. Instead of giving a prenatal diagnosis negatively, doctors would be required to provide objective information about the life of people with Down syndrome and the supports available. It’s a step in the right direction, and we hope to see such a bill introduced in provincial legislatures across the country.

You can read more about the Canadian handling of prenatal diagnoses in We Need a Law’s position paper Aborting Those Who Are Different. If you live in Nova Scotia, send your MLA a SimpleMail asking them to support Bill 56. If you live in another province, ask your MLA or MPP to introduce similar legislation in your province.